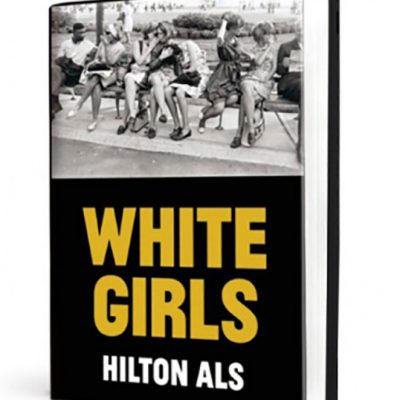

Lilly Markaki on why Hilton Als’s White Girls still matters

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

It must have been a month ago. I was back in Athens, talking to a friend of my mother’s, who was saying her mother didn’t care about the old women in x village, or how they used to put on a smile and gather around a big fire and sing, while sticking their washing in some great, common receptacle. She wasn’t from that village, she had moved there upon marrying her husband, and so why should she care about their way of doing things? In private conversations, these women would perhaps comment on her attitude, understand it through some sort of superiority complex, but the truth was that their ritual just wasn’t who she was.

It’s a few days later, and I finally decide to pick up White Girls, a collection of short stories and essays by one of The New Yorker’s finest staff writers, Hilton Als. The book is not new; it came out in 2013, and was also shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award of the same year. But I never got around to reading it, and now I’m on vacation, and I’ve been carrying it about everywhere I go and it’s time.

Published here for the first instance, the opening essay, “Tristes Tropiques”, packs so much in, that it can feel a little disorienting. Yet, somehow, this doesn’t make it a difficult text for the reader; Als’s language is incredibly compelling and, by the time I’m finished reading, I find myself submersed deep into the author’s world – one that’s simultaneously a portrait of late twentieth-century American life and culture. “We were the twin boys – one dead, one not dead – in Thomas Tryon’s fantastic 1971 novel The Other,” he writes of his relationship with his friend and lover, SL. “We were, in short, colored male Americans, a not easily categorisable quantity that annoyed most of our countrymen, black and white, male and female alike, since America is nothing if not about categories.” [1]

Though predominantly a story about love and desire, this first essay in a collection of thirteen navigates through an array of complex questions around race, gender, and identity, more generally, setting the tone for the rest of the book. And, while it’s true that “the subtlety of [the text’s] thinking is wedded maypole-fashion to a real confessional lyricism,” [2] as J. J. Sullivan has observed, how much of the protagonist is truly Als, or Als reflecting on a younger Als, becomes of little importance once such ideas come into play.

“Daddy turns me on because he doesn’t think I’m cute; he makes me work for his admiration. He knows that I spend a lot of my time at the big lending library at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, reading books. What he doesn’t know is that while there, I also listen to recordings by grand actors reading famous poetry, prose, and plays as a way of learning how to speak in an authoritative, gentile way meant to captivate my father, like a pus-y siren. I listen to white girls such as Glenda Jackson as Charlotte Corday in Peter Weiss’s play Marat/Shade … She contradicts my family for me.” [3]

Read this without going back to your own childhood, the ways your parents’ presence (or absence) shaped your being the way you are – to your own Glenda Jackson. It’s impossible. Part of this story’s energy comes, of course, from the fact that Als appears here completely unafraid in expressing himself: “I was a gay man who did not suck white dick: I refused on the grounds that the world sucked them off well enough.” [4] But then there are also those other instances, moments of profound sensitivity, which make it difficult to argue that there isn’t a thing such as a universal experience of being human: “What else is there but other people?” [5] And, later on:

“… I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savoury, like love. And there’s my mouth, too, and it’s filled with SL, so to speak, including his idea that race doesn’t make much of a difference at all in his world of – aside from me- women.” [6]

“I am Louise Brooks, whom no man will ever possess. Photographed in profile, or three-quarter profile, or full front, photographed and filmed for as long as I can remember … my face … a face that did not convey the vitality of youth so much as it conveyed the dissatisfaction one might have with one’s youth upon realising one’s youth is there to be ruined, capsized, and sometimes one simply just wants to get on with it,” he writes as Louise Brooks in “I Am The Happiness of This World.” [7]

Some essays earlier, in “GWTW” – this time as a coloured man and author – Als writes to cut. In looking at photographs of lynchings, he observes that:

“…it’s not hard to imagine how this is your [he means his] life, too. You can feel it every time you cross the street to avoid worrying a white woman to death or false accusations of rape, or every time your car breaks down anywhere in America, and you see signs about Jesus, and white people everywhere and your heart begins to race … like Brock Peters in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird … it’s her word against his but her word has weight, like the dead weight of a dead lynched body.” [8]

God, Als crosses streets so as not to cross me, the white girl, and I go through life hoping that I am not racist; hoping because, Rosa Parks is my hero and, yes, I love The Fugees, but being white and relatively privileged, I am not qualified enough to make that judgement. What do I know about racism? How can I redeem myself? This essay is no fun. It’s too much for me. “Don’t we want this story to go away?,” [9] Als asks in one instance, and I do, so I go on twitter. It’s three or four scrolls down and I’m looking at a tweet that reads something like this: “White privilege means not having to create hashtags like #iftheygunnedmedown.” A wave of depression crashes through me. I go back to reading.

Who are the ‘white girls’ in this book of essays about, among others, Michael Jackson, Richard Pryor and Eminem? They are, it turns out, not always white, and not always girls. “Truman Capote became a woman in 1947,” writes Als in “The Women”. [10] I won’t explain how or why he makes that claim, because I think that you should read this book, but the important thing here is that moment of clarity that the writer affords us, when one comes to realise that things are not always how they seem and that is certainly true of people.

I digress for what is, I promise, the last time: Beyoncé performs “Formation” live at Super Bowl. “Earned all this money but they never take the country out of me / I got hot sauce in my bag, swag.” The crowd goes nuts. Yet, one man doesn’t. His name is Jonathan Gentry and this is his message, delivered via youtube:

“I do know what she was doing .. there is a double standard that we do not acknowledge, that we do not address … you can’t tell one group: ‘Shit down, shut up, what you do is racist and offensive to me, put your Confederate flag away’, while we wanna parade and shove how we feel down everyone else’s throat … I am speaking to the black community, you and I know … if anyone else did a performance and it was racially motivated like hers was, we would we pissed … we would be protesting, marching, calling Obama on the phone.. we’d be calling all telling them to shut that down. So how is it that this girl could perform the way she did? [11]

It’s February 2016 and, for Gentry, Beyoncé becomes a white man.

Whether you loved her performance or not is irrelevant; my point is that gender, race and all else come to exist together in complicated ways and, like the mother of my mother’s friend, sometimes the way we are inside just doesn’t correspond to how others perceive us or expect us to feel. This is what Als is saying, I think. And, in the end, all of the writing in White Girls – be it autobiography, fiction, or essay – is about a certain process of de-subjectification; overcoming one’s assigned identity, and finding and “exercising the courage inherent in being one’s [true] self.” [12] A process that involves also forgiving, if not forgetting, the other for limiting you, some kind of letting go – what Gentry wishes Beyoncé would do: “She’s sowing seeds into the young generation, they internalise it…It’s wicked. We don’t need to go back to the past and hurt others with it,” he finally says in that youtube video.

I’m nearing the end of White Girls. The final chapter, only six pages long, bears the title “It Will Soon Be Here.” What we find here, among thoughts on language and memory and the self, is the story of a queer child “not being a boy” [13] and his mother, who, upon seeing another boy that was not a boy, will, one day, turn to him and say: “Faggot.” Now this boy that maybe is Als and maybe isn’t, will forever carry this moment and try to erase it, or at least remember it differently. Soon, he will meet a bad man who will break his body like his mother broke his heart; and this, too, he will try to forget and reimagine. Sweet surrender to, and for, love – only this one is not sweet at all:

“… for the child, the queer child some mother must have loved most, this revision of history takes place even before there is a past to be had – it takes place simultaneously with the realisation that the parent may pull the following out of his wig or hat: ‘You are no son/daughter of mine.’ To whom do we belong in this ruined kingdom we all want to belong to, regardless of how wrecked, how stultifying? To be central and apparently loved, one will do a great deal, even exercise, continually, the courage of shutting up, the conviction that yes I am just like you and everyone else or at least exhibit the desire to be … Self-censorship as the entry fee into the ruined kingdom of their existence, of lies and lies again, means a good-bye to the memory of all the cocks and cunts and hearts and minds that we embrace in our mouths, and our hearts, too, but spit before we give ourselves the chance to name them. If you choose this, all of those others who fly but fall so disastrously against the clean and wide high wall of memory misremembered may choose not to remember you, too, as the boy who … will not love anyone because that love means to remember a hate that consumes his heart; or produces such a memory of the mother saying,

‘What if your father saw you like that?’ “[14]

To be central and apparently loved. Isn’t this eternal desire to feel ourselves beloved, indeed, the great architect of all our dreams and disappointments?

Notes:

[1] Hilton Als. White Girls. (San Franscisco, USA: McSweeney’s, 2014), 14. [2] John Jeremiah Sullivan as cited in Brad Listi. “Episode 244 – Hilton Als.” URL:http://otherppl.com/hilton-als-interview/

[3] Hilton Als. White Girls, 27. [4] Ibid., 29. [5] Ibid., 14. [6] Ibid., 37. [7] Ibid., 205. [8] Ibid.,141. [9] Ibid., 141. [10] Ibid., 97. [11] Jonathan Gentry. “#Beyoncé Super Bowl performance #DoubleStandard.” URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkyBZRE_xzk [12] Hilton Als. White Girls, 338. [13] Ibid., 336. [14] Ibid., 339.