As the late and much-loved Katy Dove’s work is celebrated in a major exhibition, Neil Cooper talks to Graham Domke and Anne Marie Copestake about this most playful and visionary of artists

January 23, 2017

It’s all too fitting that Dundee Contemporary Arts’ overview of work by artist Katy Dove has moved north to Inverness, where it opened this month en route to Thurso and Wick following its Dundee run. There are few contemporary artists whose work evokes the playful spirit such wide open spaces can inspire as much as Dove. She may have lived in Glasgow prior to her untimely death following treatment for cancer in January 2015 aged forty-four, but her upbringing as one of five sisters in the village of Jemimaville in the highland peninsula of The Black Isle was key to everything that followed.

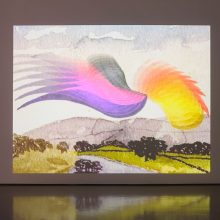

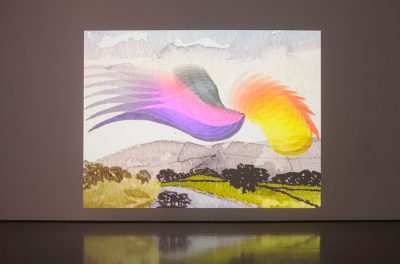

This is evident in Melodia (2002), a four and a half minute film in which Dove took a watercolour landscape by her grandfather and breathed swirling life into its skies, seas and landscapes. It was there too in Dove’s series of caravan residencies run on a farm in Balfron, the Stirlingshire village close to the Campsie Fells, with fellow artists Belinda Gilbert Scott and Sarah Kenchington. Here impromptu performance nights took place in an environment that sounds akin to an arts-based summer camp for grown-ups.

Such a physical and instinctive response to her environment is similarly inherent through the pastel-coloured symmetrical shapes that seem to dance off the surface of whatever context Dove utilised to show her work. That response is at its most powerful in the primal, percussive-based utterances let loose by Muscles of Joy, the sometimes-seven, sometimes-eight-piece band Dove played in with friends, artists and fellow travellers Anne-Marie Copestake, Leigh Ferguson, Sophie Macpherson, Victoria Morton, Jenny O’Boyle, Ariki Porteous and Charlotte Prodger. Whatever Dove created, it seems, was pulsed by a rhythmic musical sweep and a sense of child-like wonder which wouldn’t have looked or sounded out of place on Sesame Street.

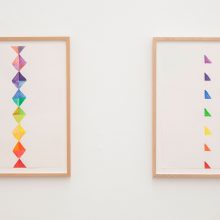

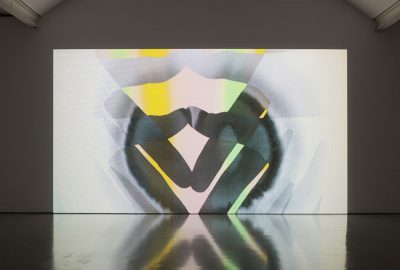

All of this is abundant in Dove’s DCA show, which puts her animations at its centre as they run on four separate loops flanked by more than forty paintings, drawings, prints and music. In terms of timeline, the animations themselves are book-ended at one end by Fantasy Freedom (1999), a ninety-second stop-motion animation made for Dove’s degree show while studying at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in Dundee. At the other, the kaleidoscopic shadows of Dove’s own hands and legs appear in what turned out to be her final film, Meaning in Action (2013). There’s little stillness anywhere in a body of work – and Dove’s artistic output is about the body as much as the soul – which, seen as a whole, appears to be moving towards ever more expansive forms of expression.

Meaning in Action, 2013

“It’s still really only a short amount of time since Katy passed away,” says the show’s curator Graham Domke, who until recently was Exhibitions Curator at DCA. “It becomes a vastly different undertaking putting on an exhibition without the artist to call upon. I had wanted to work with Katy for a solo exhibition at DCA since I worked with her in 2009 for the DCA’s tenth anniversary exhibition, The Associates. It would have been so great to have done a big show with her, but the family made this exhibition possible.

“I took the archive on loan and went through the hundreds of works. I wanted an audience of friends of the artist, new students from Duncan of Jordanstone, and total strangers to get a really positive sense of how Katy had worked. I made a decision to show as much as possible. Katy’s work was always adored by children and the DCA show was programmed to coincide with the venue’s film festival for younger audiences.”

“There’s been a really great response to the exhibition from across the board. The family and close friends were incredibly supportive. There is considerable solace and pride in looking at the exhibition and seeing Katy’s creativity. I want to stress that it is not a definitive retrospective of Katy Dove’s work. I see it as more of a primer.”

Untitled diptych 2007, oil on linen

Domke first saw Dove’s work in early shows at the Collective and Stills galleries in Edinburgh and Transmission in Glasgow. “The work definitely stood out,” he remembers, “but it was in her show at the Talbot Rice a decade ago that I really saw her hitting her stride on a big stage. Like a lot of other people, I’d learned that Dundee had been producing some of the country’s best young artists in the late 1990s. The likes of Kevin Henderson, Cathy Wilkes, Victoria Morton and Graham Fagen were young tutors at the time and there was the inspirational Alan Woods and the journal Transcript, all making the city feel very outward-looking. Ultimately that’s one of the reasons why I came to DCA in 2007, so I could tap into that rich source and show artists who had studied here such as Duncan Marquiss, Scott Myles, Cara Tolmie, Clare Stephenson and of course Katy.”

Dove was born in Oxford, and after growing up in Jemimaville, studied psychology at the University of Glasgow. Supporting herself by making and selling jewellery, she won a scholarship to Duncan of Jordanstone in 1996. After moving into sculpture, the instinctive immediacy of her already vibrant automatic drawings were crying out to be brought to life. Her first foray into animation, Fantasy Freedom, combined the rhythm of Dove’s breath and the sound of her bicycle with pulsing kaleidoscopic colours, marking the beginning of her fusion of sound and vision.

Active in artist-led initiatives, Dove’s involvement with the Unit 13 collective while in Dundee was also the start of an ongoing series of collaborations. This continued when she moved to Glasgow, where she joined the music group, Full Eye, with Copestake and Porteous, both future members of Muscles of Joy. Dove also joined the Parsonage, the Glasgow-based community choir noted for its unique cover versions.

“Katy and I knew each other through both being resident in Glasgow, and through several mutual artist and musician friends,” Copestake recalls. “I cannot remember exactly how we met, but it was some time in the early 2000s. I have footage of Katy on mini DV tapes from that time. I went through occasional phases of taking my little camera with me to things. I know we were also aware of each other as women working with moving images.”

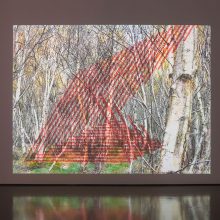

Gondla, 2005

“I think the first time Katy asked me about doing something together was in 2004, and she asked if I would write some text, creative writing, but in some way connected to her work, for a publication to accompany her solo exhibition at Pump House Gallery in London. She had seen a previous piece of writing I had done for a catalogue for Vicky and liked it. They applied for extra funding for this writing from me, and unfortunately didn’t get the funding they’d hoped for. It is quite a Katy thing that the writing did not happen then, as she was very hot on people being paid for their work and they only had funding for the more formal writing that had been arranged. In all the work or projects that I’ve done with Katy there’ve been a few similar qualities forming the foreground or background, whether it be just the two of us or in larger groups. From my perceptions, and from what Katy had said, I think Katy and I found complementary qualities in each others’ way of working that provided a strength in our projects and collaborations – complementary in the sense of enhancing the different qualities.”

“I learned a great deal about harmony and harmonies from Katy, musical and compositional. I really thrived on the exploration and testing out ideas that Katy encouraged in all art forms, and the tendency to not define too early what something was or wasn’t, the trait of not attempting to edit and create at the same time. I also really enjoyed and thrived with the, at times, more formal even reserved qualities and suggestions she brought up for consideration.”

“Although we worked quite differently, I think we had a fairly similar approach in the desire to do things – an energy given into doing, trying out, playing, making, as well as an energy given into committing time to these things. One thing we have in common is that we are both incredibly loyal, so I suppose it made sense that we worked or collaborated together pretty regularly, in different formations.”

Copestake’s experience of Dove’s caravan park residencies was of “a very generous project. It allowed complete focus on your work, if you wanted it that way, coupled with the experiences of daily life in the caravans on the farm amongst the whole little community there. There was no application process. It was a question of checking diaries. The residencies were hallmarked with the generosity and unforced presence which Katy brought to a lot of her projects. While I was there it was terrible weather. I didn’t do the long walks a lot of people did, it was pretty cold and wet. I read, did quite a bit of work, a little music. Small details really stood out in the days and nights.”

Dove’s working relationship with the natural world is something Copestake doesn’t find easy to define, but speculates from her own observations. “I noticed harmonies, discord, interference patterns, connectedness and disconnect between multiple things over limitless grounds or spaces in her work,” she says “whether that be multiple marks, sounds, movements and repetitions…”

October, 2011

Domke sees the exhibition’s transfer to Inverness, Thurso and Wick in conjunction with the High Life Highland organisation as a major component of the show’s life. “The work is returning to a spiritual home,” he says. “Katy grew up in the Black Isle and her mother still lives there, so it is really poignant that the work can be shown in first Inverness and then up to Wick and Thurso. The staff of High Life Highland have been great. Dundee is where Katy studied and found her style as an artist, and so the tour combines into something magical.” As Domke also observes, there’s plenty more of Dove’s work beyond this show. “We’re only showing the tip of the proverbial iceberg,” he says. “There are extraordinary works on paper that I really hope will enter in to public collections and go on show. I made a selection of works that I felt were indispensable for this show but there is so much still to be seen – more psychedelic, visionary, exploratory, literally illimitable! Her whole collaborative approach needs to be celebrated further, from Unit 13 to singing in The Parsonage Choir and playing with Muscles of Joy and Full Eye.”

To accompany the exhibition’s Dundee run, DCA hosted a series of one-off complementary events, with improvising musicians from Stevie Jones’ Sound of Yell project and choreographer and friend of Dove’s Sheila Macdougall responding to the exhibition. These acted as a kind of continuum to Dove’s vision that reaches beyond gallery spaces.

“Katy’s commission for the BBC Pacific Quay headquarters needs to be revisited,” Domke says, “and then there is all the inspirational work with children, her fascination with computers, a screen-saver for Transmission and an interactive drawing word with Simon Yuill.”

For Domke, Dove’s importance as an artist was due to what he recognises as “her holistic approach to art and life. I think it is significant that she had a degree in psychology before she went to Duncan of Jordanstone. I loved her ability to work with everyday materials and to take taken-for-granted utensils like a felt-tip pen or a home computer and produce revelatory, mysterious, enigmatic work with them. Her partner wrote to me describing the DCA exhibition as being ‘saturated in the sights and sounds of Katy’ and that is an amazingly succinct expression of the work. Even if you didn’t know Katy, that magical effect is transmitted from the works on view to the visitors.”

This magic was evident in Dove’s everyday life as much as in her art. As Copestake points out, “I think in life, and in many working situations, Katy really nurtured people, although they may not have known it or recognised it at the time.”

Photographs of Katy Dove’s work by Ruth Clark, courtesy of DCA and the artist’s estate.

Katy Dove’s DCA exhibition runs at Inverness Museum and Art Gallery until February 25th 2017, then at Thurso Art Gallery and St Fergus Gallery, Wick from March 4th-April 15th 2017. A catalogue published by Dundee Contemporary Arts and High Life Highland features contributions from Graham Domke, Kirsten Body, Laurence Figgis, Neil Mulholland, Victoria Morton and Katy Dove.

http://www.dca.org.uk

http://www.highlifehighland.com