The creators of Britain’s first counter cultural paper talk to Neil Cooper about their new visual catalogue of the ’60s radical underground press

November 10, 2017

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

It was fifty years ago this year that the so-called summer of love burst forth in a wave of hippy idealism played out to a psychedelic soundtrack. In the UK, much of the activity sprang from the coming together of counter-cultural forces at the International Poetry Incarnation in 1965. Held at the Royal Albert Hall, this iconic event put American beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the top of the bill featuring some of the finest (male) minds of his generation. Immortalised on film by Peter Whitehead’s short documentary film, released the same year, the IPA subsequently spawned numerous Happenings, where psych-rock bands, triptastic light shows and freaky dancing set the template for high times to come. Barry Miles worked at Better Books, where the idea for the IPA was hatched, and saw the possibility for a magazine to disseminate all the alternative ideas that were brewing around sex, drugs and rock and roll. The result of this was International Times, or IT, a playful and provocative fortnightly periodical which wasn’t so much on the scene, as simply defining it.

With an image of silent movie starlet Theda Bara as its ‘IT Girl’ logo, and featuring an editorial board that included Traverse Theatre co-founder Jim Haynes, Rutherglen-born poet Tom McGrath and other key ’60s figures, IT launched in 1966 at an ‘all night rave’ at the Roundhouse in Camden. The Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine were the star attractions on a night that kick-started a cultural revolution.

A photograph of IT’s editorial board taken by the magazine’s co-founder, John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins captured a huddled-together crew in the office, caught up in the moment and cock-sure with self-belief. They were making history, their grins seemed to suggest, and the world was about to be turned upside down whether it wanted to be or not. Hopkins’ picture formed part of Taking Liberties, an exhibition of photographs by Hoppy at Streetlevel in Glasgow, in 2009. A selection of covers from IT accompanied the exhibition, in which Miles took part in a lively discussion on the era it depicted.

Half a century on from when the picture was taken, things might not have quite worked out as planned, but the back catalogue of IT and other dispatches from the underground frontline remain key signifiers of their time. Which is why the recently published book, The British Underground Press of the Sixties, is such an essential document. Brought together by Miles with London gallerist James Birch, the coffee table-friendly volume may on one level be an accessory to the recent exhibition of the same name at Birch’s A22 Gallery in Clerkenwell, London. But it’s also a vital handbook to underground culture in the pre internet age.

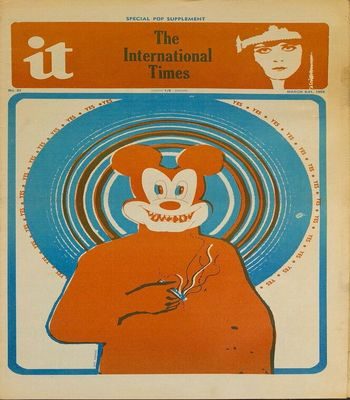

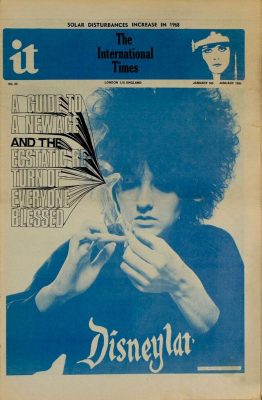

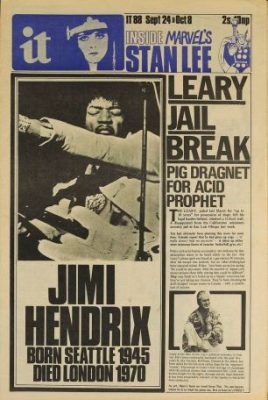

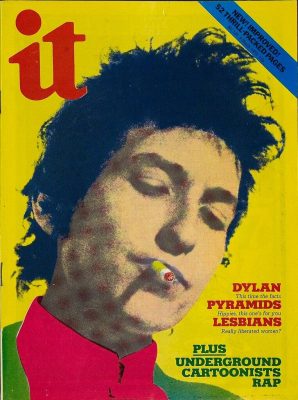

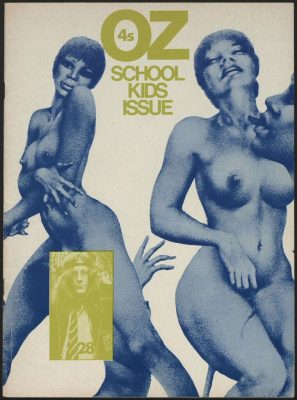

Over more than 200 glossy pages, The British Underground Press of the Sixties reproduces the covers of 174 issues of IT published between 1966 and 1974. Alongside this are front covers of some of the key magazines spawned by IT, which may have been fellow travellers, but also show the various shades of alternative thought that were bubbling under. This includes the covers to 56 issues of the trip-tastic Oz, as well as the comic strip offshoots of both magazines, Nasty Tales and cOZmic Comics.

The book also features selections from the more whimsically-inclined Gandalf’s Garden and its Tariq Ali-edited Marxist flipside, The Black Dwarf – a title co-opted by Product for a column in its original print incarnation, no less. There are illustrations too from Friends, which began life intending to be a London arm of Rolling Stone before mutating into Frendz. Also in the mix are covers from Ink, Australian emigre Richard Neville’s post-Oz project. Like Frendz, Ink struggled against the tide of a more downbeat 1970s, as the underground was absorbed into the mainstream.

With each section introduced by short histories of each publication, the various documents, posters and other ephemera from the IT and Oz archives that acompany them conspire to create an eye-dazzling primer of mind-expanding radical thought and the explosion of artistic life that went with it. If the restless kaleidoscope of pop art and psychedelic-inspired graphics look like another world, the book has been a long time coming.

“It’s a project that James and I have been talking about for seventeen years,” says Miles. “We were originally going to do something at the British Library as part of something that looked at the counter-culture in a much broader way. This is just magazines and posters, although we’ve extended our remit into the comics published by IT. The idea was to show stuff that people have never seen; newsagent’s cards and other ephemera, just to give a sense of the visual ideas of the underground press.

“It was also the fiftieth anniversary of the summer of love, and the fiftieth anniversary of Oz, and it all seemed to come together at the right time. When I went to art college in the 1950s, Paris in the ’20s was only thirty years ago, but it felt like a completely different world. Now, we’re further away from the 1960s than we were then from Paris in the ’20s, but unlike previous eras, people are still around, the stuff is still around, and, probably most importantly, the ideas are still around.”

Much of the reason for the latter is down to Miles, who’s been one of the great chroniclers of late twentieth century counter-culture, having penned numerous tomes, including volumes on Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Frank Zappa. Closer to home, Miles has also written a counter-cultural history of London since 1945, and books on the Beatles and Pink Floyd, as well as a look at the ’70s underground scene in London and New York. While Miles has immortalised numerous legends of the counter-culture in words, crucially, The British Underground Press of the Sixties focuses on its visual identity.

“Visually, we stole stuff wholesale,” says Miles. “Art Deco, Aubrey Beardsley, American pop art, pictures of Victorian children, they were all in there. Most of the people doing it were very recent art students, so the stuff they were influenced by hadn’t really been digested or filed away. One day you could go to the pawn shop and pick something up, you would mix it up with something else, then the next day it would be in IT or Oz.”

All of the images in The British Underground Press of the Sixties come from Birch’s personal collection. As an art dealer and gallerist, Birch gave Grayson Perry his first solo show in 1984, and later exhibited Gilbert and George. At the A22, he has showed the likes of former Throbbing Gristle provocateur, Genesis P-Orridge. Before all this, Birch trained in the Old Master department of Christie’s Fine Art in London, where he established the 1950s Rock and Roll department. Such an array of off-kilter interests may well stem from Birch’s first experience of the counter-culture when, as a thirteen year old year old in search of enlightenment, he picked up a copy of Oz.

“I thought it was amazing,” he says. “There were some great magazines around, but nothing as explicit as Oz. What was interesting in Oz was how it used art and surrealism. At that time, if you went to a gallery, you couldn’t really see surrealism, so to pick up a copy of Oz, which was really surrealistic, and which you could buy on the street, was a real eye-opener.”

As the utopian visions of the 1960s faded into something greyer, the ideas of the underground press trickled down into the mainstream in a way that could either be regarded as selling out or subverting from within. This happened first through the then thriving music press, who co-opted the counter-culture’s attitude by hiring writers and artists from the underground press. Writers Mick Farren and Miles from IT, Nick Kent and photographers Pennie Smith and Joe Stevens from Frendz, and Charles Shaar Murray, who contributed to the notorious Oz schoolkids issue, all moved on to NME.

While one of the final editions of IT during its 1977 incarnation (The British Underground Press of the 1960s only documents covers up until 1974, when the magazine originally shut up shop) declared that ‘Punk is Dead’ it was this new noisy youth culture that picked up the underground’s then slightly strung-out baton. This came through a cut and paste aesthetic in cheaply Xeroxed fanzines that defined a brand new visual style and seemed to gob on everything that came before it. As with the underground mags that sired them, the music press copped their attitude and gave its writers a future.

IT itself has been brought back to life several times. A new print edition began publishing in 2016, and an extensive archive of every issue of IT can be found online. As for anything resembling an underground press today, “I think that’s you, isn’t it?” says Miles. “A lot of similar kind of material is obviously online, but things are so different now that you can’t really make comparisons. There are plenty of people who get up everybody’s noses, still. The police are always infiltrating animal rights groups and other groups, but a lot of the stuff we were doing has become more acceptable.

“Back then, it was the beginning of the ecology movement and vegetarianism, collective living was becoming a thing, and there was a greater acceptance of the idea of being a multi-cultural society, although that’s taken a bit of a set-back lately with Brexit. Things are much better now than when I first came to London,when there was really only one culture, and there were very few people who deviated from it. Arguably it was the beginnings of the women’s movement, and a whole variety of sexual preferences were being explored in ways that, today, has helped homosexuality become acceptable in society. But everything was different then. The first flat I lived in when I came to London didn’t have electricity, and if you wanted to meet up with people or have a party, you’d send people postcards all the time.”

In this respect, the counter culture has arguably gone mainstream in a way that both Miles and Birch see as a positive transformation.

Birch recognises how “It’s inevitable that things become institutionalised in some way, but it’s important this stuff has a wider reach.”

Miles puts it more simply. “We wanted to change society,” he says, “but we never wanted to be in a ghetto. I think the world has changed enormously, and part of that came directly out of the underground press.”

The British Underground Press of the Sixties, edited by Barry Miles and James Birch, is published by Rocket 88 press, £35.

http://www.britishundergroundpress.com