Set in a near-future Earth devastated by global warming, The Book of Joan is a rare attempt to deal with a colossal issue. Sybilla Archdale Kalid on why climate change can’t be contained in modern literature

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

In The Lorax, Dr. Seuss’ 1972 allegory of climate change, a forest of Truffula trees is threatened by the corporate ambition of The Once-ler, who’s dead set on ‘biggering’ his business irrespective of the threat it poses to the environment. Back then, Trump wasn’t quite the villain he is now, but it’s amusing that the word ‘biggering’ sounds like it could have come straight from the mouth of the man who withdrew the US from the 2015 Paris climate change accord. Less amusing is that The Lorax’s warning about the potential menace of rapacious capitalism to the environment is still relevant. Yet, despite the preponderance of the climate change debate in the media, Dr. Seuss’ children’s story remains one of the few works of fiction that tackles the issue head on.

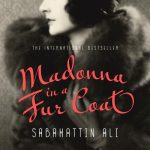

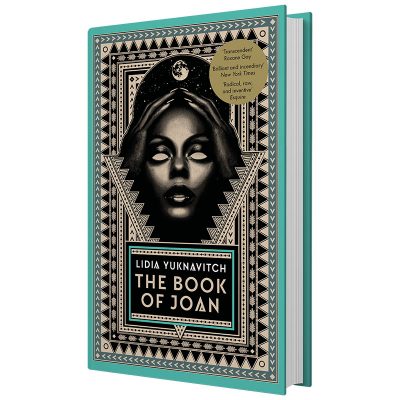

A further exception to this is Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan, Joan of Arc’s story retold in the context of a near-future Earth devastated by global warming. The novel has only just been published in the UK but has received considerable critical acclaim in the US, with The New York Times describing it as ‘radically new, full of maniacal invention and page-turning momentum’. Film rights have already been sold.

The novel doesn’t quite do justice to this expectant wave of hyperbole. It does have a refreshingly direct, contemporary narrative voice (the pages are littered with expletives), which thankfully pounces straight into a description of the world without requiring readers to follow a breadcrumb trail to an explanation of the ravaged state of the earth. It even compares the fictional disaster to the Chicxulub asteroid impact that may or may not have caused the extinction of the dinosaurs, giving the circumstances of the novel credibility. However, things veer off into a mud-bath of magical realism halfway through; one character communicates through a spider, another can walk through walls and the eponymous Joan is revealed as having the ability to harness the elements. What would otherwise have been a powerful diatribe against human corporate greed falls down slightly, as the world is no longer a convincing projection of our own.

Still, The Book of Joan is a provocative attempt to deal with a colossal, under-fictionalised issue. It’s bemusing why, when so much media and political discussion is preoccupied with the race against climate change, it’s been so little addressed in fiction. That’s not to say it’s been neglected entirely; Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl are all successful novels examining the effects of climate change. It’s surprising, however, that the biggest threat currently facing the human race isn’t addressed more frequently in literature.

That is, if it is at all; those novels that do focus on the issue tend to be referred to as sci-fi – or even ‘cli-fi’, the climate change specific sub-genre. For a start, sci-fi implies a distant, fantastical future, whereas the effects of climate change are already being witnessed. The Book of Joan, despite being lauded as ‘genre-defying’, buys into the genre a little too heavily to be a serious warning of impending ecological disaster. Human bodies are laced with inscribed stories – ‘grafts’ – and lack sexual organs, and the power-holders hover above earth on the ‘suborbital complex’ CIEL.

Further, sci-fi tends not to be considered ‘serious’ literature, and is often dismissed as ‘genre fiction’. This implies that it can only speak to a limited range of human experience, within the conventions of its genre. The irony of climate change fiction being treated in this way is that there is nothing to which we are more universally subject (albeit accounting for the unjust variation of impact between countries). So significant is humanity’s effect on the planet, that scientists and philosophers believe we have moved into a new geological epoch, The Anthropocene, which acknowledges humanity as the dominant influence on the environment. This then begs the question whether a new form of literature needs to develop to account for a new type of human experience – a new literature for a new age – or if the term ‘literature’ needs to adjust its boundaries to accept cli-fi as important commentary on the current state of humanity. ‘Literature’ is a wobbly word but, demotically, tends to embrace works considered to have intellectual or artistic merit, and typically excludes works that sit comfortably within a genre. It’s interesting that The Lorax, as one of the best known stories about climate change, is marketed as children’s fiction – another subcategory that struggles to be taken seriously as literature. Whilst Yuknavitch’s novel does shake the bars of its sci-fi cage, it’s slightly too clumsy to feel fluidly literary. It does host an ardent intellectualism, with articulate meditations on gender and social narratives, but these sit slightly awkwardly on the surface, feeding the novel’s interest in the ‘power of representation’ without letting the story really dig its nails into these issues.

Why, then, this difficulty with fictionalising climate change? One reason, perhaps, may be the difficulty of humanising it. The disparity in scale between individual human actions and their environmental consequence is so colossal that an exploration of this is tricky to explore in a literary narrative. Timothy Morton, a philosopher whose views on the inter-relation between humanity and other beings has been gaining increasing traction, refers to global warming as a ‘hyperobject’ – a word that effectively sums up the idea of it being an almost inconceivably mammoth, but equally concrete, problem.

There’s also the issue that the drama of climate change happens in a non-human, non-social sphere. Of course there is the inter-personal conflict (between, say, a Greenpeace activist and a Big Oil executive), and the fact that every time we turn a car ignition we engage in it, but this doesn’t really represent climate change itself directly. There remains a gulf between the human and the elemental. The Book of Joan goes some way towards attempting to dispel this disparity. The environment is humanised in the form of a sort of earth mother – Joan – whose ability to channel the energy of earth and air is related to a glowing blue light on the side of her head. Funnily enough, this connectivity between body and earth chimes with Morton’s ideas; one of his central theories is that for centuries humanity has seen itself as an entity distinct from its environment, and we are only just waking up to interdependence with other natural beings.

However, The Book of Joan’s preoccupation with the bodily is as much an interest in gender and sexuality as in The Anthropocene. On this, it’s at its most eloquent. Despite genderless, asexual bodies, vestiges of gender remain. A faux-medievalism trickles through the relationship between protagonist Christine and her Renaissance-man lover, Trinculo – ‘“Come here this instant, you reeling-ripe dove-egg”’, he says at one point – creating a palimpsest of archaic gender dynamics. In this way the ravaged earth becomes a means of sifting through the dregs of humanity, working out what is essential.

It also poses one of the questions at the heart of the climate change issues: is the future of humanity really worth the sacrifice of other types of life? The villain of the book, Jean de Men, is engaged in a project to reignite human sexuality and reproduction, but in doing so has created a ward of bodies deformed by crude attempts to craft sexual organs.

In Jean de Men’s ideal future, women would be relegated to reproductive machines (think The Handmaid’s Tale), churning out further impotent offspring with no opportunity for non-procreative sex. Through the novel’s insistent linkage between the human body and earth, the desire for honest, loving human relationships feeds into a desire for more mutual, respectful relationships with the planet. The book suggests that without this, the war of humanity versus its environment creates a humanity as destroyed – and destructive – as the planet will become.