Sue Palmer hails Jonathan Haidt’s timely look at the explosion in smart phone addiction amongst children

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

IS BEING ON A MOBILE PHONE FOR EIGHT HOURS A DAY POTENTIALLY NOT ENTIRELY BENEFICIAL FOR THE UNDER TENS?

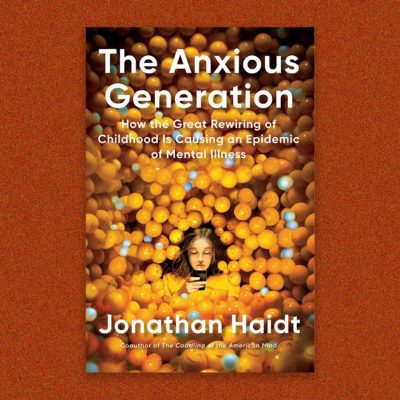

Good old Private Eye. Its take on media coverage of Jonathan Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation is spot on. If you know anything about evolutionary biology and/or child development – indeed if you’re possessed of half a brain – it’s obvious that the change from a play-based to a phone-based childhood has significant implications for children’s long-term physical and mental health.

Haidt makes a compelling case for connecting this rapid cultural change to the explosion in mental health problems among children and young people, yet scientists who advise USA and UK governments still reckon the jury is out. Might there be economic reasons for their reluctance to find out? Who knows. But until they get their act together, I agree with the The Anxious Generation’s back-cover recommendation that ‘Every parent needs to stop what they’re doing and read this book immediately’.

Play’s the thing

Haidt is a social psychologist whose first book on 21st century childhood, The Coddling of the American Brain (2018, co-authored with free speech campaigner Greg Lukianoff), was about giving children and young people freedom to play and explore, rather than subjecting them to parental and/or educational supervision and ‘protection’ during every moment of their waking lives. He was promoting – I suspect unconsciously because he doesn’t quote them – the conclusion of developmental psychologists over the last century, that children are primed by evolution to develop critical skills and capacities for themselves, in response to their environment.

For instance, during their early years – birth to eight – adults can’t teach self-regulation or emotional resilience, except by example. Children throughout the millennia have developed these capacities for themselves through active, social, outdoor play. The adults’ job has always been to provide a secure, loving base from which they can venture out to explore and experiment, and a safe haven to which they can return at the end of the day.

In a traffic-clogged 21st century world, it’s impossible for most parents to provide these free play opportunities for the under-eights, so countries that care about children’s developmental needs provide play-based kindergartens with well-qualified staff, to support their future citizens’ long-term health and well-being. There’s always a solution, as long as one doesn’t take too long in confronting the problem.

The mental health epidemic

As Haidt explains in his Conclusion to The Anxious Generation, he didn’t set out to write another book about childhood – his original topic was the damage wreaked by social media on American democracy. However, while drafting a chapter about IT’s impact on university students, he made the connection between the loss of ‘real play’ and the exponential rise of mental health problems among young people.

So the great question Haidt asks in his book is: does it matter when children’s play (in real time and space, with real people) transfers to an online world controlled by tech companies? Has there been a ‘great rewiring’ of childhood? Haidt didn’t seem particularly bothered by this particular change in children’s habits in the earlier book, but has clearly undergone an epiphany during his research into smartphone technology.

The Anxious Generation catalogues the manipulative psychological techniques used by IT specialists to turn kids into smartphone addicts and explains the neurological consequences of early addiction to social networking and/or pornography. As one who spent many miserable hours wading through this sort of stuff while on the child development research trail, I know exactly why he now feels so passionate about spreading the word.

You sense his frustration when he quotes Sean Parker, first president of Facebook, describing the stated intention of social media moguls in the early 2000s: “How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?” Apparently the founders of Facebook and Instagram knew they were exploiting “a vulnerability in human psychology” but did it anyway. “God knows what’s going on in our children’s brains,” commented Parker in 2017.

Something must be done

Seventeen years ago, I helped organise a press letter from experts in child development expressing concern about the potential ill-effects of a screen-based childhood. The Letters Editor of The Times newspaper telephoned to explain why he wasn’t going to print it: “It’s a something-must-be-done letter,” he said. “Write us one that solves the problem and we’ll consider it.”

I hope, wherever he is, he reads The Anxious Generation. It has a whole section entitled ‘Collective Action for Healthier Childhood’ with plenty of sensible suggestions for action (since this runs to 75 pages, it’s a bit long for a press letter or we might have tried to write one in 2007). The suggestions are aimed at:

- governments, e.g. encourage more ‘real play’ in schools; raise the age of internet adulthood from 13 to 16

- tech companies, e.g. create an age-check feature, ‘on’ by default whenever a parent creates an account for a child under 18, so children can’t fib about their age

- schools, e.g. provide more opportunities for unstructured free play, become a phone-free school

- parents, e.g. band together with other parents to provide opportunities for free play, follow accredited medical guidelines on screen time. I suggest searching for ‘American Academy of Paediatrics screentime’.

However, although schools and parents can and should take action, the power and reach of tech companies is now so great that government intervention has become essential. So, above all, I hope some of those wretchedly ignorant scientific advisers read The Anxious Generation – before it’s too bloody late.

*

Sue Palmer is a writer, childhood campaigner and founder of Upstart Scotland. Her 2006 book Toxic Childhood: how the modern world is damaging our children and what we can do about it (Orion) was one of the first to draw attention to the effects of rapid cultural change and she recently edited Play is the Way: child development, early years and the future of Scottish education (Postcards from Scotland).