A beginners’ guide to Ron Butlin’s fiction. By Alistair Braidwood

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

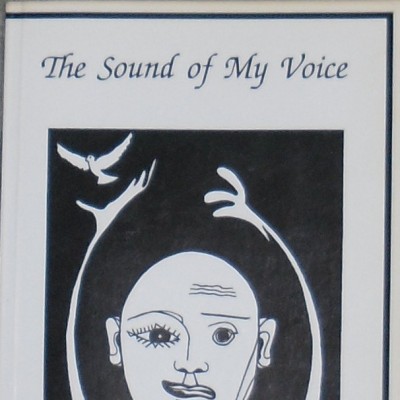

In the late ’90s a friend was looking for a Scottish novel that could become the basis of a film proposal, and one of those he considered was a slim volume called The Sound Of My Voice, the 1987 debut by Ron Butlin. This was just after the height of success by ‘The Chemical Generation’ of (mainly) Scottish writers; a group which included Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner, Gordon Legge and Laura Hird. For a while, Scottish writing was arguably more popular than at any other time since a previous chemical generation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan-Doyle and JM Barrie were literary darlings in the latter part of the 19th century. Everyone was hungry for the next big thing, but the irony was that one of the best had been around since the ’80s and was being overlooked. This situation has improved somewhat in the time since, but there are still too many people who are not aware of Ron Butlin, particularly his fiction (Butlin is best known as Edinburgh’s Poet Laureate). If you haven’t read any – and you should – then his debut, and his most recent novel Ghost Moon, are the perfect places to start, and here’s why.

That film adaptation of The Sound Of My Voice never happened, but the novel was passed on to me, and I, in turn, have bought many copies for people over the years; suggesting they read it with almost evangelical zeal. When I’m asked for a recommendation of a great Scottish novel, this is my number one choice. As a piece of writing it’s a master class, written in second-person narrative throughout. I imagine this was a mentally exhaustive undertaking for the writer as the book demands the utmost concentration from the reader. The result of his narrative technique is disorientating and disconcerting. It’s written in a manner that is not only unusual but, importantly, is uncomfortable. However, it is not simply an exercise in literary style. What makes it great is the story and how it is treated.

In 2002, the Village Voice asked Irvine Welsh to write about a lost classic novel. He chose The Sound Of My Voice, which he proclaimed as “one of the greatest pieces of fiction to come out of Britain in the ’80s”. He went on to say, with relation to the book’s relative anonymity, that “Butlin’s book was perhaps ahead of its time for the ’80s; its unremitting, if implicit, criticism of a spiritually vacuous, socially conformist age are far more unsettling than many of the more celebrated, overtly polemical works of fiction Scotland produced at this time”. For once Welsh was not dealing in hyperbole. The Sound Of My Voice is as devastating a critique of the emptiness at the heart of Thatcherite ideology as you will find. What is perhaps unusual is that not only did Butlin not set out to achieve this, until Welsh pointed it out he had never realised his book could even be read this way.

In a recent interview, Butlin admitted that this political aspect of the novel hadn’t occurred to him. Inspired by an alcoholic acquaintance, for him it was the very personal story of Morris Magellan, a relatively successful businessman who is struggling, and failing, to come to terms with his own alcoholism as the façade of his external life clashes with the terrible reality of his internal one, and the glue of alcohol becomes toxic. Butlin set out to examine how some people manage to maintain such a deception when their reality is something else altogether. He wanted to try and understand the limits of such a self-delusion and the destruction this can wreak. The thing is, both men’s readings are correct.

All of Butlin’s novels are a mixture of the personal and the political, and it depends on the reader as to where the mean is between the two. His latest, Ghost Moon, is ostensibly a story of Maggie, a woman we meet near the end of her life, who had to fight for herself and her son in her youth as she was shunned by family and friends. She has to deal with being an unmarried single mum in a time and place, Scotland in the post-war years, where being such was to become a pariah.

Butlin said that the reactions he has had to the book, from readers and from audience members at readings, has moved and surprised him. Women who were abandoned by their families after falling pregnant, those who gave up children under duress, and even women who had cast their daughters from their homes believing they were doing the right thing, have all contacted him to relate their stories, and the strength of their feelings of guilt, abandonment, and despair, often decades later, have given the book a following that Butlin did not expect. But then, I don’t believe he ever writes with a reader in mind, and he almost seems surprised when his books strike a chord with others. These are stories about ordinary people going through extraordinary times which he feels compelled to tell, and it is for this reason they prove to have such far reaching appeal.

Heroism is often too obvious and glib in fiction, but Maggie’s is tireless and resolute. Some may argue that her actions are selfish, but those people must be cynical in the extreme. Butlin’s triumph is to make the reader desperate to know what happens next, and how Maggie deals with everything put in front of her. She is an unforgettable creation from a writer who again proves that he is one of the best around.

In a similar manner to Welsh’s reading of The Sound Of My Voice, by focusing on one woman’s struggle in Ghost Moon, Butlin shines a light on how the weakest and most vulnerable in society were treated during a period of austerity, something we would do well to reflect upon today. Those who do not fit in with the neat narratives of acceptable behavior are often removed from sight, forgotten about, or simply ignored as conservative values take hold. Although the inspiration for Ghost Moon is a very personal one, in writing it Butlin has again asked us to consider carefully what is morally right rather than simply accept what we are told is acceptable and the norm.

His other novels, Night Visits and Belonging, and short story collections The Tilting Room, Vivaldi And The Number 3 and No More Angels, are all worth hunting down, and his poetry is exceptional, but The Sound Of My Voice and Ghost Moon are the essential texts. James Kelman said that the greatest drama is to be found in ordinary people’s everyday lives, and Ron Butlin is not only interested in real lives, he manages to present them in a manner which is both artistically and philosophically challenging.

His work moves people because the writing is shot through with a humanity that will strike a chord with most socially and culturally engaged people. Tell a story with truth and honesty and it will in turn ring true to the reader, and Butlin is determined to be true to his characters, and to himself. What sets him apart from most is that he challenges his readers to do likewise. This is the briefest of introductions, but, by concentrating on the two novels which bookend the career to date of a remarkable writer I hope you will be persuaded to read Ron Butlin. You’ve got nothing to lose and a whole lot to gain.

Find out more about Ron Butlin and his work by visiting his website or listening to Alistair Braidwood’s podcast interview with him on the very fine Scots Whay Hae!