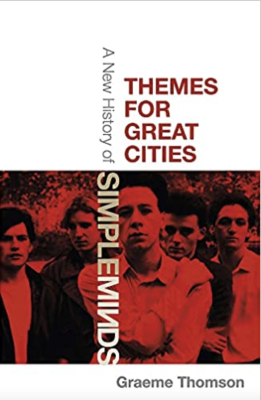

Alistair Braidwood admires a fresh look at how Simple Minds created their early innovations

February 11, 2022

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

Simple Minds were the Scottish band who conquered the globe, taking their place, in the mid-late ‘80s and into the ‘90s, on the stadiums and megadomes of the world; with albums which would often top of the charts in any number of countries, and whose songs were ubiquitous across national and international radio stations. They were the first band invited to play the Philadelphia leg of Live Aid, were central to the legendary Mandela Day concert at Wembley Stadium in 1988, and appeared on the soundtrack of John Hughes’ most celebrated movie, The Breakfast Club.

For many this is the Simple Minds they recognise, but, increasingly, it is their early recordings – Life In A Day, Real to Real Cacophony, Empires and Dance, Sons & Fascination, Sister Feelings Call, New Gold Dream (81/82/83/84), and Sparkle In The Rain, which are feted by fans, critics, other musicians, and even by the band themselves, as ground-breaking. It does seem that the critical acclaim they received was/is in inverse proportion to their global success, which makes them one of the more interesting bands to ponder and discuss.

Graeme Thomson’s biography Themes For Great Cities: A New History of Simple Minds acknowledges this, focusing on the early years of the band and their music. Lauded music journalist and writer Thomson has previously written biographies of Kate Bush, Phil Lynott, John Martyn, and George Harrison, amongst others, but this feels like a more personal undertaking which allows for a gratifying balance between journalistic rigour and the enthusiasm of a genuine fan. Or perhaps I’m projecting my own fandom onto the book, as those albums also mean a lot to me.

If you own any of them then you will know how arresting they are, still sounding, on the whole, unlike anyone else (more or less – so much music was being made over such a short period that not everything stands the test of time).

What Thomson offers, often through interviews with band members and others who were there, is the stories behind the music. These unfold at a pace, which is unsurprising considering the seven albums mentioned above were recorded and released over five years, between 1979 – 1984. That’s comparable to the time it took fellow Glaswegians The Blue Nile to release A Walk Across The Rooftops (1984) and Hats (1989) (two faultless albums to this writer’s ears).

I am not suggesting for one moment that making music should be either a marathon or a sprint, or any such comparison – I am comparing the two for another reason, something which emerges from Themes For Great Cities. Both The Blue Nile and Simple Minds used their shared home city as inspiration for their music in very different ways. Compare the former’s ‘A Walk Across The Rooftops’ to the latter’s ‘Waterfront’ – two great songs about Glasgow released on albums in 1984. The first is a delicate, ethereal, piece of music which captures the sounds and sense of the city at night – a three in the morning existential meander through empty streets. ‘Waterfront’ is a bombastic paean to the River Clyde and the work which was once its lifeblood. Two sides of a city which, in the early ‘80s, was rarely depicted in modern music, or elsewhere – although that was changing.

The influence of place and people on the music of Simple Minds is something that Thomson manages to clarify in this history. The overriding feeling about them at the time was that they were a European band – one who looked to the krautrock of Neu!, Can, and Tangerine Dream, and later Kraftwerk, and the synth pop of Giorgio Moroder, for inspiration – making you both think and dance, a rare combination. As well as the music, Thomson makes clear that this love of all things European was as much due to the books they were reading and the films they were watching, but also from trips to the great cities. This was a band who found their inspirations everywhere – cultural sponges desperate not only to consume but to contribute.

What many didn’t realise at the time (at least it passed me by) was that they saw Glasgow as one of those great European cities, a good decade before it earned the title of ‘European City of Culture’ in 1990. They were artistically reflecting the city around the same time as writers such as James Kelman and Alasdair Gray were doing likewise. There’s a quote from Gray’s 1981 novel Lanark which has been used often, but is worth repeating here:

“Glasgow is a magnificent city,” said McAlpin. “Why do we hardly ever notice that?” “Because nobody imagines living here…think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.”

Somewhere in that quote is a rallying cry which Simple Minds intrinsically understood, and from the start they were imagining, and reimagining, Glasgow alongside those cities and others. Thomson unpicks and clarifies this idea through the lyrics, music, and individual reminiscences, and such fresh appraisals are another reason for reading his book, and for revisiting the records.

The twin driving force of Jim Kerr and Charlie Burchill are key to the pace at which the band grew and progressed, a Glaswegian version of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Glimmer Twins’ of Jagger and Richards. It becomes clear that while they wanted all the members of Simple Minds to be equal, some were more equal than others. But the book more than acknowledges the contributions of other members, especially Brian McGee (drums), Michael MacNeil (keyboards), the mighty Derek Forbes (bass), and many, many more, and most are interviewed for Themes For Great Cities. This is a central aspect to this new history of Simple Minds, which offers as many points of view as possible. Thomson manages to get honest reflections from his interviewees, and there seems genuine fondness for those times, and for each other, from all involved, which lends the book a warmth which it may not have had otherwise.

The one important voice missing for me is that of drummer Mel Gaynor who came in around the time of Sparkle In The Rain (and who didn’t want to be interviewed). It’s a shame as his drumming, which is a thing of rare power and poise, changed the band notably as they moved towards the bigger sound they felt was required for the larger venues they aimed to make their home. Whatever your thoughts on the music they went on to make, few bands can reach the back of an audience as Simple Minds, and the aforementioned ‘Waterfront’ is perhaps the key example of both the move from one style of music to another, and of Gaynor’s influence.

While Themes For Great Cities is an engaging, insightful, and welcome biography and history of one of Scotland’s greatest bands, it is important to remember that they are still going with Kerr and Burchill to the fore, touring and making new music – much of which reflects these early records. There are only a few bands who last long enough to influence themselves, but that seems to be the case with Simple Minds. If you only know their work from the massive hit single ‘Don’t You Forget About Me’ (and there are great stories surrounding that), Live Aid, Mandela Day, or their first, and to date only, UK number one, ‘Belfast Child’, then Themes For Great Cities: A New History of Simple Minds may well change your mind about the band and the influence they had on some of your favourite music. If you don’t know them at all you are in for a treat, and this is a great guide as to where to start. If you were already a fan it’ll make you return to those glorious early albums and fall in love with them all over again – the ultimate accolade for any music biography.

Themes For Great Cities: A New History of Simple Minds by Graeme Thomson is published by Constable.