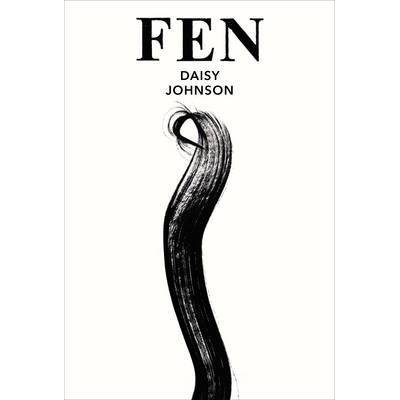

Daisy Johnson talks to Naomi Richards about the power of myths, metamorphis and the art of writing her new novel.

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

Naomi Richards: The unexpected seems to just appear in your stories, such as the fox baby in How to Lose It or the mother making her mud babies in Birthing Stones. This popping up of what is mythical and strange is a delightful feature of your short stories. What’s your intention by drawing on myth?

Daisy Johnson: There are so many writers who do draw on myth or fairy tales, it’s something people return to again and again. For me, I think, there is a sort of joy in rewriting, in the challenge of it. The first rewrite I ever read was Roald Dahl’s reworking of fairy tales. They are so glorious and silly and dark and I loved how they utterly revelled in telling these old stories in different ways. My first novel, Everything Under, is also a rewrite of a myth and I think I started it because I wanted to see if I could do it, if I could take a myth so totally of its time and make it contemporary, see where the boundaries of change and possibility were. Another reason that FEN returns to myths is that there is just so much interesting fodder to use. I listened to the Greek myths on audio book when I was young and they’re bursting with metamorphosis and weirdness. They inspired me a lot.

NR: Tim O’Brien, writing about the art of storytelling said stories “should push into the unknown in pursuit of still other unknowns.” Do you feel this is a useful way of thinking about the art of storytelling?

DJ: I think as a writer there are certainly worse ways to go into writing than as explorers, attempting to find the boundaries and push beyond them. Short stories are still on the outside and as peripheral figures perhaps they are in a better position to explore these areas. Tim Lott wrote scathingly in the Guardian about literary fiction but with the world in such flux it’s impossible to think that writers will continue to write in the way they always have, following traditional structures of plot and style, will not adapt and try new things.

NR: Would you describe your writing as speculative fiction or do you prefer not to categorise?

DJ: As an ex-bookseller I think categorization is excellent; as a writer perhaps not so much. We seem, as readers, to be continually trying to limit what we will or will not read. The amount of times I’ve told people that FEN is a collection of short stories (although even that’s up for debate) and they’ve told me, sometimes apologetically, that they don’t read short stories. I’m as guilty of it as anyone else, of sticking to what I know, but I’m trying to be better, to spread my reading further afield.

That’s an unhelpful answer to a good question. My writing is always going to be populated with weird, unreal, strangeness because of the people I’ve read and because, really, I can’t see how the world can be described any other way. I love the idea of speculative fiction, of how broad and possibility- filled the term is.

NR: Water is often a motif, existing as a sort of liminal space or state, such as in Spring and in some of the stories in Fen. What draws you to using the element of water in your writing? Boats and babies also feature a lot – are there any connections between the two?

DJ: In the writing of FEN it was inevitable that water would feature heavily. The fens are an area of farmland that was once underwater and then were pumped dry. I grew up in that area and part of its intrigue for me was the idea that this was land that was once under water, that remembered being under water. But you’re right in that water is a continued motif for me, in stories after FEN, such as Spring, and also in my novel which is set in part on a river based on that around Oxford where I now live. I’ve tried again and again to work out what it is about water and why it’s something I return to. Perhaps it’s that water, particularly British water, is murky and it’s almost impossible to see what lies beneath. So there’s fear there and also endless possibility: because really anything could be beneath the surface.

In noting boats and babies you have picked out a big theme in the novel. I know that I’ve got a bit of a thing about mothers and maternity and children. I think it’s impossible not to when growing up in a world where women’s choice when it comes to children is such a public, twisted thing. And so perhaps there is something about boats and freedom, or boats and unconventional lives. And again, perhaps, the interlinked fear of children on boats, on tenuous ideas of safety.

NR: Your teenagers are unnerving, intense and brilliantly drawn. Do you voice teenagers because they exist in a liminal space between childhood and adulthood? What are the difficulties in working with a teenage voice?

DJ: I think I first started working in the teenage voice because when I lived in the fens that’s the age I was. But the more I explored it the more interesting I found characters who exist in that place. You’re right, it is a liminal space, not quite child and not quite adult. It’s a messy age, filled with blood and firsts and high emotion. The difficulty I suppose is the same as writing in the voice of anyone different from the writer. Though I remember that age I am no longer anywhere close to it. I want to be authentic and true in my character explorations. I don’t believe in “write what you know” but I do believe in fully understanding what you’re writing about.

Another interesting issue I’ve started to think about as I explore other teenage characters it that of technology. There is always something new, everything in the technological world is outdated almost as soon as it appears. One of the reasons that some contemporary teenagers are so interesting is because of how close to this technology they are, how many of their experiences are through the mode of, for example, social media. This is not something I explored in FEN but I’m starting to think about it now, what is the language to talk about technology?

NR: In How to Fuck a Man You Don’t Know you mention that the main character speaks “in aggressions and facts bullet-pointed enough to cut”. How far would you say this is a description of your writing and of contemporary fiction?

DJ: Certainly some of the writing of FEN was fuelled by anger and despair and I think that comes across in the writing. I also think that short stories are often characterized by spare writing, stripped of excess. There just isn’t room in a short story for a single word that doesn’t do its job. An article in The Bookseller this week pointed to a rise in short story collection sales in the UK (hurrah!) and perhaps that stripped back style is slowly seeping into the wider world of literature. There’s also an agonizingly slow move to make sure that contemporary published work addresses minority voices that are often othered and I think that writers are trying to look for new modes and styles of writing, ones, perhaps, that are stripped of tradition.

NR: Your stories deal with the strange, the absurd and the terrifying. You deal in the excess of the imagination but it never feels excessive. Do you think that’s to do with your pared down language style?

DJ: I find it really hard to speak about my style. Obviously it is something I – as every writer does – have worked really hard on but it is also mostly a consequence of everything I have read and reread, of films I’ve watched, of dreams (I have night terrors) I’ve had, of conversations I’ve had with people, of books on writing I’ve read. So while I’m really glad that the writing style works with these stories I almost feel as if I’m unable to take credit for it. I do think the more you write the more you discover what works and what doesn’t work with your style. And you, obviously, hone that style and read new things and hopefully become a better writer. There is also, of course, something to be said for the fact that the subject matter grows with the style, hand in hand, and so it is really impossible to separate them.

NR: Neruda said that poems should be an earthy mixture of real things and the impurities of daily life. Your stories are also an intriguing mix of the earthy: of sex, sweat, what’s raw, clogged, impure and the transcendent. What effect do you think this has on the reader?

DJ: The effect I wanted to have on the reader was that they felt, even though incredibly strange things happen in the stories, that this was a world like their own and people like them. I think this is something a lot of short story writers do incredibly well; the juxtaposition between the mundane (as you say the sex and the sweat) and the extraordinary. As a reader reading writers like Kelly Link and Karen Russell the affect of this is that you almost don’t notice something strange has happened, it’s snuck in under your radar.

NR: I was struck by your startling use of contemporary imagery to describe the natural world, such as the ‘Kohl eyes of swans’ and the ‘badger-haired man.’ At other times humans give birth to, change into or look like animals, or animals can become death-like figures as in The Superstition of Albatross. How far do you trace your writing to Ovid’s Metamorphoses?

DJ: As I said earlier I love those myths and was hugely inspired by them. One story in particular, Heavy Devotion, was written because I wanted to explore the rape stories which appear so often in ancient myths. These are often stories where women are silenced and that’s something I wanted to break into and turn around.

NR: Some of your stories focus on how language escapes or fails us or how we try to control things through language but we never can, does this reflect your view on the role of the writer?

It’s something I return, often unconsciously, to again and again so I think it must be at the forefront of my mind. On a personal level though I’ve always loved language and reading I also am an awful speller, have never been officially diagnosed as such but am most certainly dyslexic. And so perhaps some of my interest comes from this battle for clarity that I go through most days.

As a writer it’s impossible to fully translate the idea in your head to the page. And part of this is perhaps because language is limited, can never quite say everything that we, as humans, experience. I recently watched the film Arrival and was taken with the idea that our language changes the way we think. It’s an idea that, I believe, has become outdated in linguistics but it’s a fascinating one all the same. We think a certain way because of the language our parents use, it also follows from this that the language we use is only really able to explain our own singular experience. Language is always going to fail at going any further than that.

NR: Is there a link between your new novel Everything Under and some of the reoccurring motifs in your stories, such as canal boats, myth and writing about language? Could you comment on making the

transition from short story to novel?

DJ: I think I’ve accidentally answered most of your first question above but yes, though very different this novel is obsessed with many of the same things that FEN is obsessed with. It’s about a lexicographer (a person who writes the dictionary) who goes on a journey to find her mother and as she does so begins to remember her strange upbringing in a boat on the river. It’s about the impact of our family on us and about loss and, as with FEN, very much about language and the power it has.

The transition from writing short stories to writing a novel was both enlightening and incredibly difficult. To put it into perspective, loosely, FEN took probably about a year to finish, perhaps a little longer, while Everything Under has, from conception to final draft, taken maybe four. On a simple level a novel is just longer and therefore trying to hold it all in your head at once is a lot harder. What is also harder is the editing process. 80,000 words is a lot more to rewrite and shuffle around than 6,000. This doesn’t necessarily mean that novels are harder to write than short stories. I know a lot of short story writers would disagree with me on that.