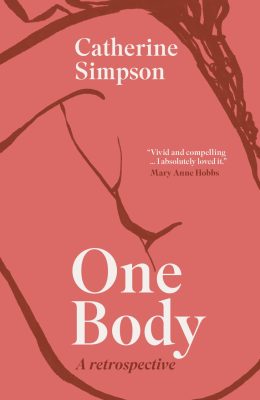

Author Catherine Simpson’s remarkable work ranges across short stories, fiction and memoir. She discusses Alan Bennett, grabbing writing time and why details matter

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

What was your first story published and how did it feel to have achieved that? The first story I got published was a piece of memoir called Mercy Boo Coo which was included in the Sottish Book Trust’s 2011 Family Legends’ anthology. I was invited onto BBC Scotland to read it and be interviewed. The whole experience was a wonderful baptism of fire. I was doing an MA in Creative Writing at the time at Napier University and had started taking my creative writing seriously two years before, aged 45, when I began studying writing with the Open University. Getting Mercy Boo Coo published when I was 47 years old made me think that maybe getting a book published wasn’t a pipe dream.

Can you tell us one of the most surprising things you learned in creating your books? I love writing because it is a solo pursuit. I like being on my own and I am never lonely. The most surprising thing I have learned in creating my books – one novel and two memoirs, plus various short stories and poems – is how much teamwork is required. From my agent to my publisher, from early readers, copy editors, cover designers, publicists, book sellers and many others, it takes a whole team to get the book to the reader. This seems obvious now, but I used to fantasise about being a writer who roamed around in her own head all day, left to her own devices. The writing life is like that sometimes, but I’ve learned that I love all the collaboration it takes to get a book on the shelf. I’ve also got to know a big writing community in Scotland which is wonderful and extremely supportive.

Is there anything you know now about your career that you wish you knew when you started out? My writing career started late, and I’ve never had a plan. I like it that way – I’m glad I don’t know what’s round the corner. I apply for all sorts of opportunities and most of them come to nothing – then some lovely offer arrives out of the blue. It is good to be proactive, and to throw your hat in the ring for different projects, but it’s also nice to let things unfold in their own time. Having said that, when I was starting out, it would have been nice to know that I would eventually get a full-length work published. My first novel was short listed for the Mslexia novel competition in 2010 but was never published. It got me interest from my agent though, so that was a big step. I think many, probably most, writers have unpublished manuscripts tucked away somewhere.

Do you have a particular approach to how you create the structure of your novels, or is each one different? I don’t have a set approach for structuring a book – they have all evolved in different ways. It can be quite a painful process involving much rewriting. I don’t plan a book, I just start writing, so the first draft is me working out what I’m trying to say. Then subsequent drafts are shaping the material, shifting chunks around, building bits up, cutting bits out, honing the writing to say as much as possible with as few words as possible, making sure the language is true to the characters and places I’m portraying.

Does writing affect how you think about the future? Writing helps me make sense of events in the past. It makes me understand myself and the world better.

If you could steal a painting from anywhere in the world to hang above your writing desk, which would it be? I love art galleries and use them a lot for inspiration. One of my favourite paintings is Three Oncologists by Ken Currie which is on display at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. I write about this painting in my next memoir One Body a book that includes my year with cancer and looks at how our bodies tell the stories of our lives. Three Oncologists is such a mesmerising portrait though, that I would never be able concentrate on my writing if it hung above my desk. Instead, I’ll take Lady Agnew of Lochnaw by John Singer Sargent which is on display at the Scottish National Gallery. That lady knows things. She has stories to tell, and she makes me want to write them.

When you approach your desk in the morning, do you ever find yourself wanting to run screaming in the opposite direction? If so, how do you get yourself to sit down and start writing? When I’m in the middle of a project I try to write 1000 words a day but some days I despair that I won’t make it. I am not a fast writer. I need a lot of thinking time, a lot of reading time, research and preparation time. When I have done enough of that the writing is easier. If I feel as though the words aren’t coming, I read a writer who inspires me: Jenny Diski or Joan Didion for example and soon the desire to write grows strong. I love the editing process much more than the writing of the first draft. All that fine tuning – reading aloud to myself, checking every sentence – is right up my street.

What is your work schedule like when you’re writing? My life is quite full with caring responsibilities, so I don’t have such a thing as a writing schedule. I have learned to grab the odd half hour whenever I can. In fact, I can probably write as much in half an hour as half a day. A bit of pressure does me good. I recently wrote a piece for Radio 4 which was agreed with the producer on the Friday and delivered on the Monday. Pressure is quite exciting – you never know what it will create. I love writing workshops for the same reason – you have to write something then and there, which can be nerve wracking but always produces words that wouldn’t otherwise have been written.

If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be? I would tell my younger self to take more notes about the details. I was an obsessive diary writer as a teenager but wrote the most generalised rubbish so there is very little of use in them. I should have written down the exact phrases people used, the exact meals that were eaten, clothes worn, etc. Writing is all about the authentic details. Photographs of the everyday are good too – not just special occasions. I always have a notebook to hand to write down the exact details – the sounds, sights, smells, textures of the hospital, the church, the corner shop – anywhere.

What are the ethics of writing about people you know? When writing memoir, it is inevitable that you include real people. This is the most difficult thing about it. Of course, the first thing is you must not libel anyone, but beyond that you should also consider people’s privacy. Changing names or using initials may help – but I’ve found that the best thing is to let the person know they are included in the book and show it to them prior to publication. Surprisingly you may find that their objection is not being included enough, rather than being included at all! If people dispute your interpretation of events this can become part of the story – a demonstration of how fallible memory is and how we can only experience things from our own perspective. It is impossible to libel a dead person, so if I am writing about someone who is deceased, I ask myself: is this true? is this fair? is this necessary for the story? Writing One Body felt very much ‘my’ story and I felt freer writing it than I had when writing When I Had a Little Sister which obviously included my sister’s story.

Is there a book or author, who inspired you to become a writer? Discovering Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads monologues on the television in the eighties was a revelation – there were women characters who spoke like my mother and grandma. There were characters talking directly to the camera and telling all kinds of stories that they didn’t even realise they were telling – quite magical. I bought books of the monologues and read and reread them trying to see how they worked: the black humour, the exact words and phrases, the rhythm of the speech, the pauses and the breaks. To get to read my own dramatic monologue Driving Dad to the Old Folks’ Home on BBC Radio 4, forty years later, was a dream come true. I love performing my own work – I have just recorded the audio version of One Body which I loved doing. The characters I write about are often from Lancashire and it is imperative the accent is authentic! I write occasional poems for performance too which is a buzz all of its own.

Which book has most to say to us – amidst all our challenges – at the end of 2021? I don’t know which book has the most to say to us as we stand like rabbits in the headlights watching 2022 approach at speed. I have the desire to read steady and considered voices, voices of writers echoing down through the ages – maybe Meditations by Marcus Aurelius who was known as the last of the five good emperors, or Letters from a Stoic by Seneca.

You followed up your debut, Truestory, a fiction novel, with a memoir. It’s a very different discipline. Did you approach the writing process in a different way? With each of my three books I started by writing about the thing that needed to be written about. Simply that. I wrote the scene that was at the forefront of my mind and demanding to be put down on paper, and I carried on from there. With Truestory the thing I needed to write about was raising an autistic child, with When I Had a Little Sister it was the death by suicide of my sister, with One Body it was how critical illness can make us reassess our bodies and our lives. Truestory was inspired by my own experience of raising my daughter Nina. However, I did not want to invade her privacy, so I fictionalised the issues I was interested in exploring. Whereas with When I Had a Little Sister and One Body, I was not worried as much about invading privacy, and it felt right to write memoir. With One Body the only privacy I am invading is my own and I’ve decided I’m 58 and old enough to tell the truth.

One Body will be published in April 2022.