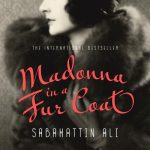

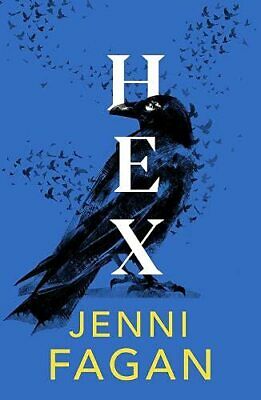

Writer Jenni Fagan discusses her new book Hex, witchcraft and the problem with magical realism

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

Listed in Granta 2013 as one of Britain’s best young novelists, Jenni Fagan is a unique, standout voice in contemporary Scottish fiction. Like much of her previous work, her new book, Hex, is gothic and centred around individuals marginalised by society. Her 2021 novel, Luckenbooth, followed the stories of the inhabitants of an Edinburgh tenement across a century, featuring an array of characters including Ivy, a bisexual WW2 assassin and Levi, a young, black American working in the bone library of the Royal Dick Vet School. They’re representative of the lesser told stories of Scotland’s past and present, with the gothic backdrop of Edinburgh a perfect match for Fagan’s writing style. Her best-known novel, Panopticon, is a dark and gritty account of a life in care, sparkling with biting humour and lyricism. Like Anais – the queer, streetwise narrator of Panopticon – Fagan grew up in the Scottish care system, spending much of her childhood in foster homes. She went on to gain a PhD and has written novels, poetry and screenplays.

Hex gives a poignant new perspective on Scotland’s notorious North Berwick witch trials, initiated in 1590 following a forced confession from a maid servant, Geillis Duncan. A witch hunt that snowballed, the accusation led to the arrest and torture of large numbers of people – predominantly women – with many subsequently burned or hanged. Hex follows young Geillis on the last night of her life, where she is visited in prison by a stranger who has travelled from the future, a place where women remain persecuted and oppressed for who they are.

What drew you to writing about an accused witch?

The first time I was asked in class, when I was a little kid, what I wanted to be when I grew up I said a witch. I was about six-years old and I was obsessed with anything remotely occult, I have no idea why. I have had a lot of strange and unexplainable experiences my entire life so the energy or idea of wiccan, or occult, or pagan practise always made sense to me. I have studied witchcraft both in practise and its history on and off all my life. The witchcraft trials in North Berwick, and indeed across Europe and the world were such a pivotal time in history. Many of the legislations and superstitions that peaked at those times still impact to this day. I did a PhD in structuralism and as a Dr. of Philosophy just extended what I have been doing all my life — observing how wider societal structures impact on the individual. Accused witches really epitomise some of the most brutal aspects of that experience.

Geillis is a wise, young, working class girl but her most striking attribute is her incredible strength. Once you had researched her, how did you go about developing her character?

I give over all my time and energy to the characters as much as I can, try to find their centre rather than my own. Geillis was a real person and that was what I wanted to try and capture as respectfully and naturally as possible, whilst completely aware that I did not know this person and what right did I have to engage with her story at all. It is a fine line and I go by instinct then research a lot. I am not a historical writer in the sense where I adhere to facts solely and just write about the characters from an entirely research based view point. Hex is a work of fiction that allows the past and present to collide in a literary way.

Hex and the Luckenbooth both contain the supernatural and magical realism. What draws you to the mystical?

I never consider anything I do magic realist, it’s a term I struggle with altogether. It is often used to dismiss any reality that is not scientifically proven, or orthodox Western, white, hetero-normative, coming from some place of privilege of some kind. There is no single version of reality that deems everything else as magical. We live in a universe over 13.9 billion years old and we have no idea what we are doing here or what happens when we die. The suggestion we have it all figured out is so far from where the human race is at present, we are made from the carbon of stars as is every single thing you see each day. Just because you don’t understand something does not mean it does not exist or that it is merely ‘magical,’ thinking.

Your characters are often queer or non-binary – what draws you to writing from these particular perspectives?

I am queer. I don’t like to write solely from perspectives that are completely fixed because mine is not.

Your work features characters marginalised by society, for example characters who are trans or black. How do you go about writing from such varying perspectives authentically?

With humility and a core focus of commonality in the human condition first and foremost. I grew up in the care system and I never met anyone I was related to, or who looked exactly like me, or had the same characteristics. I was an outsider in every family, every house, every community I ever lived in. I don’t ever sit down and think that I want to write about someone who is marginalised though. I always try and write about someone who I find interesting, who has a story, and who I feel lucky to spend time working with in that book.

As well as being a writer, you’re also an artist. What artists and writers inspire you the most?

I am inspired by countless writers and artists, for art I would include: Raqib Shaw, Tracy Emin, Frida Kahlo, Cornelia Parker, Carl Karni-Bain, Polly Morgan, Leonora Carrington, Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Kim Gordon, Yayoi Kusama, Leonor Fini, Max Ernst, Francis Picabia, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Louise Bourgeois, Doris Salcedo, Marina Abramović. As for writers Dorothy Allison, Claudia Rankine, Warsan Shire, Eileen Myles, Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Derek Owusu, Kafka, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Reinaldo Arenas, ZZ Packer, Sylvia Plath, Jessie Kesson, Elizabeth Smart, Angela Davis, J.G. Ballard, Bell Hooks, Lydia Davis, Audre Lorde, Esme Weijun Wang, Irenosen Okojie, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Elizabeth Bishop, James Baldwin, Iain Banks, Jeanette Winterson, Janice Galloway, Wallace Stevens, Danez Smith, Breece D’J Pancake, James Kelman, Tom Leonard,Yelena Moskovich and Helen Oyeyemi – there is an endless list after all of these, it’s always being added to.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am finishing final edits on my memoir Ootlin, I am working on several new television series that I can’t quite talk about yet. I am getting ready for my sixth poetry collection — The Bone Library to come out in Autumn. I’m also off to Glasgow Film Festival to see the premier of a short film I wrote and directed, called Heart of Glass.

Hex is published by Polygon on 3 March