Allan Brown suspects his iPod Randomiser knows a little more than it should

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

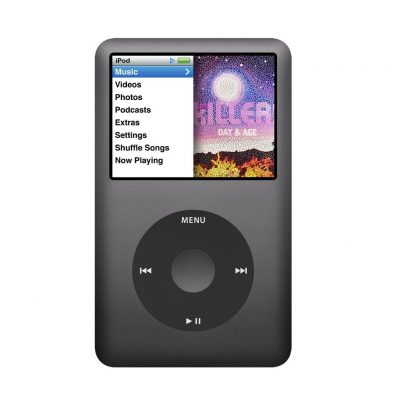

Seven hundred thousand people received iPods for Christmas last year and, by my reckoning, 350,000 of them now believe there is something very strange going on with the space-time continuum. That little white box, no bulkier than a Victorian cigarette case, isn’t merely a miraculous device for storing hour after hour of music. It also seems to have….well, let’s call them powers, very strange powers indeed.

“Any technology sufficiently advanced” Arthur C Clarke wrote “is essentially indistinguishable from magic.” Few gadgets bear this out better as convincingly as the iPod. For pod is a very Clarkeian sci-fi sort of word, isn’t it? From inter-planetary sleeping pods to landing pods to breeding pods, the pod is a classic signifier of new worlds being explored. The word also has an organic quality, as in peas. Combine both senses and you begin to approach the essence of the iPod, its defining character of organic futurism.

But there is also something more, something weird. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey, of course, featuring HAL-9000, the disconcertingly wilful supercomputer. By whatever magic the Apple corporation has at its disposal, every iPod seems to carry its own inbuilt HAL-9000. The future is now, and it wants to destabilise your diodes.

For Luddites and iPod virgins, some brief explanation is necessary. The iPod is able to store whatever music is you load onto your computer; simply connect it by means of a Firewire cable and the musical contents of your hard-drive are transferred automatically. Depending on the size of your iPod’s memory you now have up to 10,000 songs in your library. These can be organised by album or by artist; or the various tracks can be compiled into playlists, the electronic equivalent of the compilation tape. Or you can elect to have the device play whichever songs it chooses. This involves engaging the Randomiser function. And this is where the weirdness begins.

The Randomiser, then, seems to know what you’re thinking and sets out to create a musical dialogue on the subject. It knows the sentimental associations that exist between certain songs and certain places and plays them whenever you approach. It knows the historical relationships between certain performers and plays their songs back-to-back like a digital matchmaker. It develops obsessions with particular artists out of all proportion to the number of their songs you’ve downloaded.

All in all the iPod randomiser appears to have its own impish consciousness. An increasing volume of testimony (and, rest assured if you bought an iPod you’d soon be thinking like this) suggests that a new information-age urban myth has emerged, an anecdotal precursor to the eventual proliferation of artificial intelligence. The iPod randomiser appears as the synthesis of personal freedom within technologically prescribed limits, like an edition of Desert Island Discs hosted by HAL-9000. With apologies to Koestler, it is the ghost in the Tin Machine.

Of course, a simpler explanation could still be advanced. The human mind works by analogy; it is trained from its outset to recognise patterns, templates, and recurrences. This habit is the foundation of all irrationalist thinking, and by extension metaphysical belief. We’ve all experienced the strange frisson of recalling an old acquaintance then bumping into them the next day, and we’ve all wondered What It Might Mean. We habitually infer significance from the merest of pretexts, without ever considering that a world in which coincidence did not occur would be infinitely stranger than the one in which it does.

The Randomiser provides a salutary reminder of this. By presenting us with patterns and recurrences on an hourly basis it inadvertently forces us to acknowledge the delusional traps and snares of irrationalism. Sad to admit but my iPod knows nothing of the stormy relationship between Echo and the Bunnymen and the Teardrop Explodes and does not reflect it by playing them back-to-back. It is me who infers meaning from a random pattern, as we all do, virtually every moment of our lives. The iPod is an anti-superstition machine, a device to expose the fallacy of primitive thinking. And perhaps this is the most futuristic thing about it.

This article first appeared in Product’s Ideas Issue, April 2004.