Neil Cooper unearths The Red Crayola’s great lost album and post-punk’s missing link

March 13, 2019

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

1979 was a seismic year, both musically and politically. Punk’s first burst three years before had been a youthquake waiting to happen. The fatal overdose of former Sex Pistol Sid Vicious in February ’79, however, put a symbolic full-stop on the unruly non-movement’s nihilistic intent. For a generation set adrift against a landscape of industrial unrest, large-scale unemployment, three-day weeks and power cuts, it was now time to create rather than just destroy. The strikes and strife of the so-called winter of discontent that saw in the year were accompanied by freezing weather conditions that gave things an even more dystopian air. The murder of Airey Neave in an IRA bomb blast, and the death of Australian teacher Blair Peach after being ‘struck unlawfully’ by a member of the Metropolitan Police Force’s Special Patrol Group while at an Anti-Nazi League demonstration against the National Front, compounded an over-riding feeling of dread.

The Conservative Party’s landslide election victory five months later put Margaret Thatcher into 10 Downing Street as prime minister. While Thatcher’s elevation was arguably the beginning of the downward spiral that would leave us in the mess we’re in now, the Shakespearian referencing of the winter of discontent was all too appropriate.

The phrase, taken from Richard III, had first been applied to the crisis by writer Robin Chater in Incomes Data Report. It was picked up by Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan, who used it in a speech before the tabloids turned it into sensationalist headlines. Either way, the discontent signalled a cultural revolution that would galvanise resistance.

This was self-evident from some of the era-defining albums released that year. 1979, after all, was the year of Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division, Public Image Limited’s Metal Box and Entertainment by The Gang of Four. Wire’s 154 and Secondhand Daylight by Magazine added nuance and texture to the post-punk palette, which was broadened in different ways by The Clash on London Calling.

There were full-length debuts by The Human League with Reproduction and The Mekons by way of The Quality of Mercy is Not Strnen – another Shakespearian reference. The Slits released Cut and The Pop Group put out Y. The B-52’s let loose their eponymously named first album, as did This Heat. Blondie released their fourth opus, Eat to the Beat. Talking Heads their third, Fear of Music. As a portent of things to come, The Fall knocked out their first two albums within six months or so, with all but one of the band surviving Live at the Witch Trials alongside Mark E Smith to make it onto Dragnet.

Looking to an older generation, Fleetwood Mac followed their Me-generation classic, Rumours, with the far kookier Tusk, while Neil Young punked it up on Rust Never Sleeps.

Two of the biggest albums of the year spanned the generational divide even more. Off the Wall was Michael Jackson’s first record in his guise of what passed for being a grown-up in his world. Pink Floyd’s similarly named The Wall, meanwhile, was Roger Waters’ mid-life conceptual purging of childhood baggage.

There was one record, however, rarely mentioned in dispatches of its time. The margins it occupied acted as a feeder to everything that came after.

Soldier-Talk by The Red Crayola was a record I first encountered in Backtracks, the second-hand record shop round the corner from the far cooler Probe, just off Mathew Street and a stone’s throw from Eric’s club in Liverpool.

Backtracks, like most second-hand record shops, was a fascinating mish-mash of unwanted Christmas-present trash and misunderstood obscurities. Given its locale, the shop was even more of a musical Aladdin’s Cave. It was the place where would-be scenesters offloaded records by weird 60s bands they’d bought in Probe after reading Julian Cope wax lyrical about how weird and groovy and psychedelic they were, only to discover they were just a bit too weird. The Doors, Love and the first Velvet Underground album were all well and good, and The Seeds and all the Nuggets bands were cool as well, but The Red Crayola?

Backtracks was where I’d already bought a second-hand, barely played copy of White Light White Heat, but it wasn’t just confined to weird 60s bands. There were always copies of Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of The Titanic and Discreet Music by Brian Eno, both released on Eno’s Obscure label, in there as well.

Most of all, Backtracks always seemed to have multiple copies of both of the original Red Crayola’s re-released 1960s albums, The Parable of Arable Land and God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It. What was it about those records that made people want to get rid of them so quickly, and why had they bought them in the first place?

Maybe they’d read the same article I had in a long forgotten free-sheet I’d picked up in Virgin over at St John’s Precinct. The newsprint-based paper featured a densely printed centre-spread featuring three separate articles, one on The Red Crayola, one on Scritti Politti and one, rather oddly on The J. Geils Band. The latter’s stadium-size hit single, Centrefold, was three years away yet, but they still made strange bed-fellows with the other two bands.

I was already aware of Rough Trade, first by seeing a filmed profile of the then fledgling label made by Simon Frith for ITV’s Sunday night arts strand, The South Bank Show. The film was screened in May 1979, three weeks after Margaret Thatcher had been voted in as PM.

Despite Thatcher’s landslide victory, ripples of protest remained. The word ‘alternative’ was at a premium, and while it’s easy to see now the cultural continuum between the hippy and punk counter-cultures, in the so-called year zero firmament of the latter, anything and everything was up for grabs. Everyone involved in Rough Trade looked like they were part of some samizdat cell involved in the production and dissemination of subversive material. Which, of course, they were.

Despite or because all or none of this, the South Bank Show film woke up my fourteen-year-old self to all kinds of possibilities. Stiff Little Fingers, Essential Logic, The Raincoats and Robert Rental where a world away from Top of the Pops punk, and by the time I heard the C-81 cassette almost three years later I was an NME-reading, John Peel listening geek who had gone down the DIY cottage industry indie label rabbit hole hungry for the next small thing.

C-81 was the first cassette compilation produced by the NME in a co-production with Rough Trade, with both parties riding on the back of the rise of the Sony Walkman, the portable tape recorders that revolutionised how music could be listened to on the move.

The C-81 cassette was free, but rather than being sellotaped to the front cover of the paper, NME readers had to save up six cut-out coupons before sending them off with a postal order to cover the postage costs, then wait a whopping twenty-eight days for delivery. That’s a two and a half month wait before you could hear any of the twenty-four tracks contained on the cassette.

Scritti Politti opened it with The ‘Sweetest Girl’, The Red Crayola were in there too, as were Pere Ubu, Essential Logic and The Raincoats. There were tracks too by Cabaret Voltaire, The Gist, Subway Sect and James Blood Ulmer, with Virgin Prunes, Robert Wyatt and Blue Orchids also in the mix. Oddities by Furious Pig featured alongside non Rough Trade stuff by Wah!, Buzzcocks, Ian Dury, The Beat, The Specials and all the Postcard bands. John Cooper Clarke was recorded performing a new poem with the staff of the paper, and there was even a track by David Grant’s disco-soul outfit, Linx.

I knew most of the bands on the tape, and if I hadn’t heard them I’d at least read about them. Pressed up so close together like this, it sounded like a serious statement was being made. The accompanying ‘Owner’s Manual’, cut out of the paper each week alongside the coupons, compounded it.

The Red Crayola C-81 track, The Milkmaid, was taken from the band’s Rough Trade album, Kangaroo?, and was co-credited to someone or something called Art & Language. With a lead vocal by Lora Logic, it was probably the first thing I’d heard by The Red Crayola since discovering Backtracks.

The band’s contribution to the Owner’s Manual was the most high-brow of them all, and said something about how the song was ‘a monstrosity of détente. It is also didactic.’ The statement went on to expound on socialist realism, ‘the rhapsodic language of bureaucratic lyricism’, and how the performance of the song was ‘a didactic act by agents estranged from the materials of which it is composed.’ I didn’t understand a word, but soon discovered that deconstruction of the pop song was all the rage.

Take Scritti Politti. Their appearance in the photograph-free centre-spread of the freesheet was probably why I’d been attracted to it in the first place. In the article, Scritti singer Green Gartside was as high on dialectical debate as he ever was during the band’s Skank Bloc Bologna/ Messthetics phase, and after the ramshackle intellectualism of their 4 A Sides and Peel Session records, hearing something so honeyed and pop savvy as ‘Sweetest Girl’ was quite a shock.

Mayo Thompson of The Red Crayola cut a similar theoretical dash. His quotes were a tumble of reference points, quizzical supposition and counter-arguments turning in on themselves. With donnish articulacy he talked of art, politics, collectivism and pop music with an equal sense of serious inquiry. Unlike Gartside, he laced his outpourings with a wry humour that recognised the ridiculousness of what he was saying even as he knew it to be essential.

Thompson may or may not have covered the history of The Red Crayola’s original trio of himself, drummer Frederick Barthelme and bassist Steve Cunningham. He may have mentioned how Barthelme was the brother of novelist Donald Barthelme, and how he would go on to become a fiction writer of note himself. He probably expounded on how they formed the band as art and philosophy students in Houston, Texas in 1966, and how they signed to International Records, an independent label run by Lelan Rogers, brother of Kenny, whose impressive roster was headed up by The 13th Floor Elevators.

Thompson almost certainly spoke of how such perceived associations set off a welter of paisley-patterned expectations for the casual buyer of The Parable of Arable Land regarding what the disc might sound like. Expectations were perhaps emboldened by the appearance of Roky Erikson from the 13th Floor Elevators playing organ on one track, Hurricane Fighter Pilot, and harmonica on another, Transparent Radiation.

Thompson undoubtedly told how the record was recorded with The Familiar Ugly, a group of fifty or so friends who, in the spirit of inclusivity and democracy, performed brief ‘Free Form Freak-Outs’ in-between more formal songs. One of them, as described in the sleeve-notes, credited to a mysterious General Fox, ‘made his music by striking two match sticks together…His girlfriend kept time by blowing in a pop bottle.’

He probably spoke too about how The Red Crayola were named by underground newspaper the Berkeley Barb as the ‘bummer of the Festival’ following their 1967 performance at the Angry Arts Festival, a recording of which was later released as part of the band’s 2CD Live in 1967 set. Then there was the small matter of how kids’ crayon makers Crayola came calling with corporate claims of copyright infringement that forced Thompson and Co to change the ‘C’ of the Crayola, in America at least, to a ‘K’.

Thompson talked as well about hooking up with conceptual art collective, Art & Language. He did this first with the group’s American wing, but there were schisms, and, with his partner, artist and fellow A&L refusenik Christine Kozlov, left for England. Here, he joined with A&L’s UK wing and with them recorded the Corrected Slogans album. This was the first music Thompson had released since his 1970 post-Red Crayola solo album, Corky’s Debt to His Father.

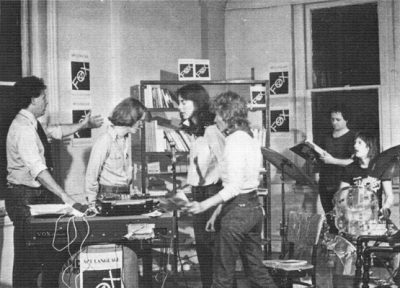

The Red Crayola with Art &Language. Mayo Thompson (left). Jesse Chamberlain on drums.

Having begun his alliance with Art & Language in 1973 following a three-year musical exile, Thompson’s revival of The Red Crayola name didn’t initially appear on the original pressing of Corrected Slogans. The record’s verbose mélange of polemic sounded like a series of mini manifestos that could have been culled from the sort of mimeographed pamphlets produced by shadowy Ladbroke Grove collectives of the era.

One could imagine Art & Language’s tracts being discussed and dissected ad nauseum before being handed out on street corners to a disinterested proletariat. Or, as was the case here, set to Thompson and drummer Jesse Chamberlain’s minimalist musical sketches.

With Thompson taking on a musical director’s role, each track of Corrected Slogans was sung/spoke/read by various members of Art & Language in plummy English post-graduate proclamations. The sense of amateur inclusivity was similar in spirit to The Familiar Ugly, albeit articulated in a very different manner. The tune to one contribution, Penny Capitalists, would later be reworked on Soldier-Talk for the song Letter Bomb.

Somewhere along the way Thompson formed an alliance with Geoff Travis and Rough Trade, and the pair worked as an in-house producing double act. After their first efforts on Stiff Little Finger’s debut album, Inflammable Material, together Thompson and Travis oversaw the first single by The Monochrome Set, He’s Frank, the eponymous debut album by The Raincoats, Nag, Nag, Nag by Cabaret Voltaire and Totally Wired by The Fall, as well as co-producing Soldier-Talk.

Following Corrected Slogans, Thompson and Chamberlain toured Europe with a duo version of The Red Crayola that would form the skeleton of Soldier Talk. Chamberlain would go on to power-pop band The Necessaries, who at one point included avant-pop-disco wunderkind Arthur Russell in their ranks.

A full live set of the Thompson/Chamberlain Red Crayola from 1978 was released in 2005 on Jean Pierre Turmel’s Sordide Sentimental label. Live in Paris 13/12/1978 contains versions of six songs that would end up on Soldier-Talk. If Conspirator’s Oath, On the Brink, Opposition Spokesman, X, Discipline and Uh Knowledge were being road-tested as they crossed borders, they already sounded incendiary.

It may have been on this tour that Thompson and Chamberlain ran into Pere Ubu, the Cleveland, Ohio-sired ‘avant-garage’ band named after the title character in French symbolist writer Alfred Jarry’s grotesque pre-Dadaist play, Ubu Roi. Led by vocalist David Thomas and at that time featuring guitarist Tom Herman, bassist Tony Maimone, synthesiser player Alan Ravenstine and drummer Scott Krauss, Pere Ubu’s first two albums, The Modern Dance and Dub Housing, had both appeared in 1978.

A third album, New Picnic Time, was released the same year as Soldier-Talk. All of the band ended up appearing on the record, alongside Lora Logic from Essential Logic providing skronky saxophone, sometime Specials side-man Dick Cuthell on trumpet, and Christine Thompson again on backing vocals.

Before the decade was out The Red Crayola had released their Micro Chips and Fish 12” on Rough Trade with a line-up that was a sort of Rough Trade All-Stars supergroup. Gina Birch from The Raincoats, Epic Soundtracks of Swell Maps and George Oban and Angus Gaye from Aswad joined Thompson and Logic. John Peel hated it. I bought it in Probe before I heard it and before I even knew about Soldier-Talk. It was hard work.

This version of The Red Crayola would release Born in Flames, a single I picked up in Probe’s bargain bin, and which formed part of the soundtrack to Lizzy Borden’s 1983 feminist science-fiction movie of the same name. If Soldier-Talk and Micro Chips and Fish were wilfully obtuse, Born in Flames was a punk-disco call to arms and gender-fluid joy.

This was made even more so more than three and a half decades later when I was fleetingly let loose on the wheels of steel at an Edinburgh post-punk night called Betamax. Playing Born in Flames to a room of late-night odd-bods expecting Blondie, I watched with Prospero-like glee as they grooved to the song’s loping rhythms and defiant sense of triumph. It was a beautiful moment, and suggested to me at least that the culture wars were far from being a lost cause yet.

Reunited with Art & Language, and with Ravenstine returning, in 1981 The Red Crayola released the Kangaroo? album. Here, with the world well and truly turned upside down, the question mark in the title was crucial.

Thompson would also go on to join Pere Ubu, replacing Herman as guitarist for their fourth and fifth albums, The Art of Walking and Song of the Bailing Man. This was Thompson perhaps repaying the favour for Ubu’s en masse appearance on Soldier-Talk. Following Pere Ubu’s departure from Chrysalis Records after New Picnic Time, both follow-up albums were released through Rough Trade, as was an official bootleg styled compendium of Pere Ubu live material, 390 Degrees of Simulated Stereo.

Some or all of this was related by Thompson, in this long-lost free-sheet in gloriously avuncular fashion via a tumble of terminally amused but perennially serious discursions. It read like it had all been bottled up over several years and refined like a fine wine before the stores were honed in assorted dispatches each time he and The Red Crayola were ‘rediscovered’.

So it would similarly prove with that copy of Soldier-Talk I eventually took the plunge with at Backtracks. According to the writing in red biro on its inner sleeve, Soldier-Talk cost me £2.50.

Both Soldier-Talk and the two archival Red Crayola records were released or re-released on Radar Records, the label set up by former United Artists A&R Andrew Lauder and managing director Martin Davis, who drafted in Jake Riviera after he left Stiff Records. As well as providing a home for Riviera’s charges Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe and others, WEA-backed Radar licenced the entire International Records back-catalogue.

As a portent of the vogue for archive-based re-release culture to come, this was possibly to get hold of The 13th Floor Elevators, with which the two Red Crayola Records may have come as part of a job lot. Tellingly, Radar also released the debut 12” by The Pop Group, She is Beyond Good and Evil, and their first album, Y.

In this way, Radar provided a brief window of entryism into the major label mainstream. Before it shut up shop in 1981, the label became a stopping off point for first wave post-punk provocateurs to regroup, recharge and reassess ideas and intent before seizing the means of production themselves. Between them, they would go on to spread their various non-aligned messages through Rough Trade and other labels including Y and F-Beat.

En route to all that, in 1978, alongside the reissues, Radar had released a 7” single, Wives in Orbit/Yik Yak, by the duo version of The Red Crayola, which also featured backing vocals by Kozlov, aka Christine Thompson, and Jane Fire of New York punk band The Erasers on backing vocals. The single was put out on voguish but conceptual red vinyl, with a sleeve designed by Malcolm Garrett’s Assorted Images imprint.

As a portent of military matters to come, it was done out in the sort of khaki camouflage that would become the dress-code of Crocodiles-era Echo and the Bunnymen and the mass of would-be romantic mercenaries who congregated in Mathew Street record shops in Liverpool. On the back, the catalogue number had been laid out like the transfer for the markings on an Airfix model Spitfire, with a blue, white and red circular target at its centre, breaking up the letters and numbers.

A flexi-disc that came free with Zigzag magazine showcased a punky re-recording of Hurricane Fighter Pilot that shared the disc with The 13th Floor Elevators.

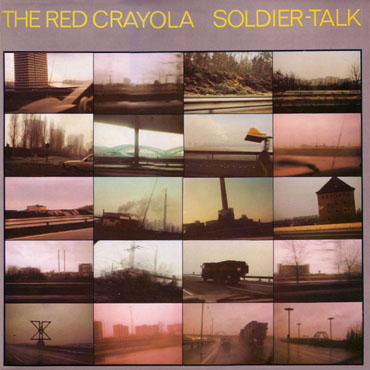

It’s still a Red Crayola with a C rather than a K that graces the battleship grey/silver cover of Soldier-Talk. The record’s cover features twenty colour photographs taken with what looks like a cheap camera in a car or van driving at high speed on the motorway/freeway/autobahn somewhere in Europe. The images are of raced-past constructions of late twentieth century industrial or post-industrial life.

Silos, pylons, bridges are all in the frame through the windshield. High-rises occupy a similarly desolate landscape. A truck drives through the rain in front of the photographer’s own vehicle. Storm clouds gather, with not a soul in sight. Seen together in the album cover montage like this, the photographs resemble out-takes from an imaginary Wim Wenders road movie set in some post-nuclear futurescape. If one was feeling particularly paranoid, it looks suspiciously like surveillance.

The record opens with March No.12, an instrumental fanfare of sorts ushered in by distorted guitar twangs, Cuthell’s trumpet blare and Chamberlain’s two-step drum-thwack before veering off into some stumblebum dance of its own design. Its wonky reveille sounds like the aural equivalent of World War Two comic strip buffoon, Sad Sack, a cartoon grotesque seriously out of step with the call to arms that had been sounded.

When the vocals kick in on On the Brink, it is with a high-pitched sense of panic, the shock and awe of impending doom almost becoming too much for its deranged protagonist. It is also the only track on the album which Chamberlain receives a co-writing credit, and you can see why. His drumming snaps and pops with a martial ballast precise enough for a parade ground gun-shot.

The Dr Phibes organ runs that open Letter Bomb give way to the nearest approximation of psych-baroque that any generation of The Red Crayola have reached. Conspirators’ Oath is powered by Chamberlain again, while Sad Sack is back out for the following March No. 14, a piano-driven recitation with a falling-down spring in its step.

Closing the first side, the record’s title track is a relentless seven-minute barrage of alarmed spoken-word barrack-room chants that saw Thompson and Thomas free-associating high-pitched babblings over restless guitar slashings before to the final squeak of Logic’s street-corner sax fades off into the distance.

Thompson sounds like a demented Dr Seuss with a head-full of theory reading a Brechtian manifesto over a marching band who’d learnt to wig-out from a Gilbert and Sullivan song-book. This helped them remain regimented enough to never lose control of the narrative’s essential form and structure. If Thompson is a deliriously insistent Seuss, Thomas buzzes about behind him, babbling twisted gobbledegook into his ear like a hopped-up Jiminy Cricket possessed by the spirit of Kurt Schwitters.

The flipside doesn’t let up, opening with the insistent Discipline. A series of mantras set to scritch-and-scratch guitar, the song concluding with wall-building zeal that ‘Might makes right.’ The record’s over-riding avant-blues twang is here emboldened by a harsher, more ornery rapid-fire approach that prods the listener into submission.

If the instrumental, X, suggests an aggressive ‘No Comment’ as the collateral damage of conflict piles up, An Opposition Spokesman pokes around the apocalyptic debris with an administrative double-think before making a break for it with a gloriously extended getaway riff. This leads to the aftermath of Uh, Knowledge Dance and the closing Wonderland, which takes a jauntily ironic skip into the celluloid sunset of a brave new world which might not quite live up to the propaganda that promised a utopian future.

All this is achieved in just over 35 pulverising minutes on a short, sharp shock of an album that sails into the heart of darkness, only to survive the wilderness and come out like Kurtz’s spin doctor kid brother.

Hearing Soldier-Talk the first time was hard to process. It was wordy. It was clever. It was terrifying. Sometimes it was funny, even as Thompson and Thomas appeared to be making speeches rather than singing lyrics.

For all the weighty-sounding monologues on what is ostensibly a concept album operetta about militarism, Soldier-Talk doesn’t simplify or sloganise. ‘Ban The Bomb’ and ‘War, What Is It Good For?’ would’ve been too easy, and had already been done anyway. The original Red Crayola themselves had jumped that particular train in their Parable of Arable Land era song, War Sucks, so why bother? Things were different now.

Cold War paranoia and the threat of the nuclear deterrent, or weapons of mass destruction as we now know them, was at its height. America was still in the throes of the fallout from Vietnam, and the peace and love generation of the hippy era which The Red Crayola had never been part of anyway had given way to something more combative on all sides. For all its spleen-venting urgency and angry-sounding barrage of post-punk sturm-und-drang, the abrasive shadows of Reagan, Thatcher and the New World Order hang over the record like a mushroom cloud.

But what ‘was’ it? I certainly didn’t know. What I did know is that whatever it was, I wasn’t ready for it yet. It was too much like hard work. But even as I put it back in its funny looking sleeve and back on the shelf, neither was I going to be defeated. I wasn’t going to be like the ones who gave up their barely-listened-to chance-buys to Backtracks and went away with much less than £2.50, feeling embarrassed by having to ’fess up they weren’t up to all that difficult music, but purged of the responsibility at the same time.

It took me months to go back to Soldier-Talk. By then, the 1980s had arrived in earnest, the world had been turned upside down in ways it wasn’t meant to and music had changed with it. Soldier-Talk sounded different this time out. It wasn’t protest music exactly, and it certainly wasn’t easy listening, but neither had it been compromised by the all-prevailing market forces that now seemed to be the only things that mattered. In a political climate where the Falklands War was looming and conscription seemed a very real possibility, as well as a cure-all for mass unemployment in the UK, Soldier-Talk now sounded like an act of defiance.

Today, it can be seen as the missing link between 1960s out-there experimentalism and anything-goes post-punk barricade-jumping, taking in ideologically sound fringe theatre inspired pre-punk prog en route. Soldier-Talk is a set of wilfully opaque show-tune grenades that take the deliberate discomforts of Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt as far as Thompson and co could carry them. They may take no prisoners, but it sounds like a blast.

What happened to The Red Crayola after Soldier-Talk I had no idea at the time. Beyond the Rough Trade stuff, live versions of X and Discipline from Soldier-Talk later appeared on Three Songs on A Trip to America, recorded in Cologne in 1983 by a line-up of Thompson, Chamberlain and Ravenstine.

Thompson’s later production work with the likes of The Shop Assistants, Primal Scream and The Chills filtered in and out of view, but I only really rediscovered The Red Krayola by way of a renewed swathe of activity in the mid-1990s. By this time, Thompson had long left London to embark on adventures in music and art in Germany and America.

With Thompson again the band’s only constant, the Red Krayola re-boot was kick-started in part by David Grubbs of Gastr del Sol, which led to a slew of new records and reissues through Drag City Records in Chicago.

Just as Thompson cherry-picked a super-group from the Rough Trade roster, a revolving Red Krayola line up has been drawn from artists on or around Drag City and a wider Chicago scene. At various points, Grubbs, his former band-mate in Gastr del Sol Jim O’Rourke, Tortoise’s John McEntire, Tom Watson of Slovenly and George Hurley of Minutemen have all played as part of The Red Krayola. Thompson has also released several new collaborations with Art and Language.

Archival Red Crayola material released by Drag City includes the original line-up’s previously unreleased second album, Coconut Hotel. This was rejected by International for being too out-there, but which now sits with ease alongside a new generation of experimentalists raised on pure noise.

In 2007, Drag City released a CD reissue of Soldier-Talk. The label’s website describes it as ‘petit guignol’, a phrase derived from the notion of grand guignol, itself drawn from the Paris-based theatre, the Grand Guignol, and co-opted into theatrical parlance as shorthand to describe the sort of OTT stage melodrama designed to shock. As a petit-guignol, then, Soldier-Talk presumably intended only the mildest of shocks.

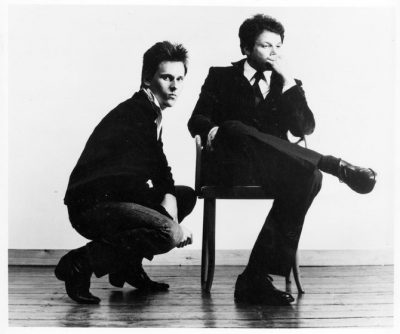

The Red Crayola as seen on the cover of the Drag City reissue

Even so, Soldier-Talk is probably the most extreme Red Crayola album. By the same token, it is also the rockiest. This is why its abstractions, when they come, sound so disarmingly subversive. Here, The Red Crayola is a band of mutineer pranksters, messing up the paintwork from within. Soldier-Talk makes demands of its listeners, even as it risks scaring them away.

And yet, and possibly because of this, Thompson sounds re-born on Soldier-Talk, his mojo well and truly re-discovered, reclaimed and lobbed into the post-punk melee like a word-powered grenade just to see what might happen. In execution, the record sounds at times like a baby boomer army brat’s attempt at institutional assassination by way of a premature mid-life crisis. What is clear from Thompson’s extensive canon, both before and since Soldier-Talk, is that he is a collaborator, aesthetically, politically and musically. It’s worth bearing in mind as well that Thompson learnt both piano and bugle while at military school, so in some respects he actually was that soldier.

Much later, Thompson landed in Scotland, where he recruited ceilidh band accordionist Charlie Abel into the fold for the Red Krayola’s 2006 album, Introduction, before decamping back to America. Since then, two new collaborations with Art & Language have appeared. The most recent of these, 2010’s Five American Portraits, bridges several generations of Red Krayola personnel, with the Raincoats’ Gina Birch rejoining the fold. I hope Mayo Thompson is causing a perennially amused commotion wherever he goes.

Forty years on from buying it in Backtracks, Soldier-Talk still astonishes, terrifies and amuses me in equal measure. It’s explosive mix of order and chaos, of discipline and dissent, of conspiracy theory and absurdist prat-falls is a vital document of its era.

When my old vinyl copy isn’t sitting on the shelf nestled between The Red Army Choir and Lou Reed – which seems aesthetically as well as alphabetically pleasing somehow – it doesn’t sound quite so shocking anymore. Heard in historical context, it seems the rest of post punk either caught up with it or else were running along beside it before taking the great leap forward.

Either way, now there are other artists who are just as complex, just as conceptually inclined, just as clever and ridiculous. Without Soldier-Talk, Thompson, The Red Crayola and all who sailed with them, might not have happened in quite the same way. The fact that former Minutemen auteur Mike Watt is known to be a fan of Soldier Talk speaks volumes. As do The Missingmen, Watt’s trio with Tom Watson and drummer Raul Morales, who in live shows channel some of the record’s skewed logic and glorious contradictions.

The sound of ‘79 probably didn’t start with Soldier-Talk. Mayo Thompson and The Red Crayola nevertheless lit the fuse on an incendiary device that enabled a slow-burning cultural revolution to explode outwards. Time was marching on. The clock is ticking still. So stand to attention, then fall out before everything goes boom!

Images courtesy of Mayo Thompson and Drag City Records.