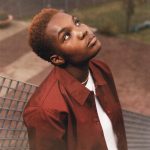

Vashti Bunyan fled the 1960s music business to roam Britain on a horse and cart, leaving behind an album of such intense beauty that it became an international cult hit 30 years later. Sylvia Patterson welcomes back folk’s most talented absentee

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Support independent, non-corporate media.

Donate here!

There are hippies, dreamers, eco-vegan sensitive souls and then there’s Vashti Bunyan.

“The pure life is a very difficult life to live,” chuckles the 60 year old minstrel down a transatlantic phone-line “and you can become so extreme. I became very extreme. To the point of apologising to vegetables before I cut them. Y’know? I’d be ‘everything has the right to be on this Earth therefore what gives me the right to stop this broccoli from reproducing itself by cutting its flowers off?’ Extreme! It got to the point where I could barely be alive myself…”

Imagine a music so pure, so delicate, so whimsically deft it darts through your window like a single sunbeam, dancing through the dust, scattering in slow-motion like a handful of wheat across the gingham bedspread of a bare-foot Goddess in the summer of 1969. Vashti Bunyan’s music is far less tough than that. Her debut album, Just Another Diamond Day was released in 1970 to universal silence, an album which began selling, finally, in 1997 (as a bootleg on eBay, before its 2000 re-release, for a decidedly impure £600), a beguiling, pastoral soundscape of almost-Elizabethan vocals, over flutes, harpsichords and acoustic guitars, painting a sun-streaked water colour of the rustic fields of Britain, all rivers, peat, magpies, lily ponds and pebbles transforming into sand. Thirty-five years later, her second album, Lookaftering (2005) was surely the most belated follow-up in musical history; her winsome atmospherics turned widescreen through piano, strings and emerging confidence in a melancholic rumination on love, loss, motherhood and sacrifice in the floury rolling pin. She’s the toast, today, of the global nu-folk uprising with a personal new friend in the Larry The Lamb of Folk, Devendra Banhart, who had her guest-vocal on his album Rejoicing In The Hands Of The Golden Empress. Today, the London-born, now-Edinburgh-living sprite-of-the-wind is in Los Angeles, a surprisingly giggly 60-year-old awaiting the birth of her first grandchild while reeling, still, from the shock of creative acceptance, at last.

“It’s just extraordinary,” comes a warm, southern English voice with a hint of Highland Scot, “I think the reason it’s happening now is because there’s a similarity to the time I left London and went off on my horse journey and left everything behind me. The world was in a similar state of unfathomable chaos and looked like it was falling to pieces. I’d shouted and protested but it felt like people couldn’t make any difference. So I thought ‘I’ll go off and make my own world’. I think that’s something that has some kind of resonance now. A small bunch of people with far too much power are taking the world in a direction most people don’t want it to go in. And maybe all you can do is try and find a little bit of peace for yourself, of warmth and safety and gentleness.”

Vashti Bunyan is the very definition of the 1960s, named after a Persian queen, a profoundly idealistic song-writer, singer and art-student in the swinging-London of 1965, Britain’s mythological pop-culture apex where “the possibilities felt huge, it was glorious“. Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ Kryptonite manager, agreed, mentoring through her debut single, Some Things Just Stick In Your Mind written by Jagger and Richards at their posturing peak who attempted, naturally, to chat her up in the studio. “Well, yes,” demurs Vashti, “but I was blind to it. I had a boyfriend! And was so shy I spoke in monosyllables.” On its release, it evaporated, to Vashti’s full bewilderment “it was totally ignored, even by my peers, which broke my heart completely”. Three more singles ensued, which were never released as Oldham lost interest, a man, notes Vashti, “with a wonderful vision but a man in a great hurry; if he wasn’t happy with the recording, he’d just move on. I felt invisible”. Already, she was retreating, laying the shaky foundations of the purist life to come, living with her art-student boyfriend Robert underneath a rhododendron bush, literally, at the back of the art-school woods.

“Well we did make a house under the rhododendron bush,” she laughs, “with a large piece of canvas. I had no money, no nothing, just this absolute bag-full of dreams and I’d met this person with similar dreams. And no money. With this wonderful idea of a house as part of the woodland. It was very beautiful. I made lovely little white muslin curtains to go all round. We made furniture out of bits of dead tree. We made little tables and chairs and a fireplace out of logs in the wood. And it was incredibly romantic and really a work of art. And we were thrown off the land. Because it belonged to the Bank of England.”

That same day, they bartered for a wagon, a horse and a harness from a local gypsy and “just took off”, their destination the Isle of Skye where fellow ’60s troubadour Donovan had created an arts-renaissance commune. So began what Vashti calls The Journey (and also The Dream), less kaleidoscopic Brigadoon reverie than a pair of dirt-poor hippies existing on pure belief. The “wagon”, in reality, was “a broken-down bread delivery van, tiny, six foot by three foot, just big enough for a mattress. But very pretty with an awning over the front and nettles growing up around it”. The Journey took 18 months.

“We believed that whatever we dreamed of was available if only we had eyes open to see it,” she muses. “If you were willing to live on so little, everything was possible. We had one sack of brown rice. We’d be given vegetables and eggs wherever we went. We made bread. And that was part of the idea of the journey, to make everything as far as possible for ourselves. And leave as little behind. Now it would be called leaving a small footprint, but that was our idea, to do as little damage to the planet as possible. Every time we made a fire on the ground we’d very carefully cut out the piece of turf beforehand and replace it afterwards. (chortles) It was kind of an experiment and it ended up being our life.”

They weren’t living, either, in some stoner’s daydream on psychotropic drugs.

“If only we’d had the money,” she guffaws, “I had to give up even smoking tobacco!”

Looking back, Vashti sees a permanent state of personal melancholy, pulled upwards only by the responsibility of looking after their horse, Bess, a horse she’d no idea would need professionally shorn every 20 miles.

“She was the main focus,” she nods, “when you live with an animal that’s so dependent on you, you completely build your life around her well being. Which was a great lesson for me because I’d been so completely self-absorbed for so long. And that was what really got me through what was probably a big depression. That was probably what was wrong with me all that time, after all that failure.”

This, really, had been a rejection of success.

“Yes. It was a rejection of everything. A rejection of everything I felt had rejected me.”

On reaching Donovan’s Isle of Skye idyll, The Dream was over, the commune dispersed, Donovan himself already living in Los Angeles, the pair then continuing on, to the Outer Hebrides. Mid-way along the journey they’d met Joe Boyd, producer behind the similarly ethereal Nick Drake. Songs Vashti had written along the way, now spurred by Boyd’s enthusiasm, formed the basis of Just Another Diamond Day which also “disappeared” on release, receiving two reviews, one good, one bad. Vashti, as artists tend to do, missed the good one and obsessed over the bad, which mocked its “nursery rhyme” qualities (possibly understandably, the chorus to Lily Pond appears to be a direct lift from Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, a gift for any reviewing cynic).

“I remember opening the music paper,” says Vashti, ” reading the review and thinking ‘yes, I was wrong, I can’t fulfil my musical dreams’, closing the paper and I never opened my mouth to sing again. And I was living with The Incredible String Band at the time.”

The creative spirit, of course, is a complex, contrary, vulnerable creature; the formidable drive to create off-set by feeble inability to take criticism, which is usually taken personally. It’s not the work that’s useless, it’s you. So it was for the chronically shy, insular, “daft and deeply innocent” Vashti.

“This person thought it was a romp through a Disney-esque landscape,” she sighs, “and it broke something inside of me. It was the response of the people around me as well. If it was ever mentioned at all it was dismissed as twee. That dreadful word. Lightweight and shallow and meaningless. And because it was my life I’d laid on the line, it dismissed a whole part of me. I was still living that life and chasing that dream. It was almost invalidating the dream. So I had to put away the musical side of the dream and carry on with the rest of it. I was putting far too much heartbreak into the music when now I had a baby to look after (a son, Leif). And a horse. And my partner. (out-break of giggling) Do you see the order I put things in? Um… don’t put that in! But I couldn’t afford the heartbreak anymore. I found all that I wanted and needed to do with my life in my child, my subsequent children (daughter Whyn and son Benjamin) and people and animals and places and ideas and dreams. I found it all out-with music. For the next thirty years.”

Life, for Vashti, has been a rolling, rural retreat, travelling through Ireland and Scotland before settling, finally, on a farmstead in Gartmore, Stirling “which we restored from the ground upward”, making a living through excavation, “making furniture out of old wood”, beginning with a stall at the side of the road and progressing to a work-shop on the farm where similarly itinerant souls would come to stay, around ten at any one time, “I had a lot of bread-making to do!” In ’92, the dream disintegrated: she and Robert split up, the two older children having already left home while Benjamin was only six. She moved to Edinburgh.

“And then I fell in love with my lawyer,” she announces, cheerily. “He wasn’t my divorce lawyer, no, because we were never married! He’d been our friend for a long time and he helped me with all the legal requirements, like selling the farm. His children knew my children and we ended up stitching our families together, into another life.”

She’d given, for decades, no thought to her previous musical life, her kids neither knowing of The Journey, nor hearing her music, until she “discovered” herself on the internet, in ’97, as some mythical, long-lost cult. In the coming years, she felt “great waves of warmth” from the burgeoning folk movement, support with her still from Devendra, Glenn Johnson (Piano Magic), Simon Raymonde, (ex-Cocteau Twins), Stephen Malkmus (ex-Pavement) and Kieran Hebden (Four Tet), spurring her on to the sublime Lookaftering, even if, for several weeks before its release, “I was hiding under my downy. And then the response was everything I’d ever wanted in 1970. 1965, even!” Forty years on, looking back, what drove her, ultimately, to live her formidably frugal life?

“Guilt,” she declares, with a peal of laughter. “Just guilt at being a human being. And the damage that human beings do. I wanted to teach myself and teach my kids that it’s alright to have nothing. That it’s alright to get by and nothing awful is going to happen to you if you don’t have a mortgage and a bank loan and a new car. You can get by with what you need and what you need is so much less than you think. You can be very very happy with very little and wonderful things happen to you which are way more beautiful than ever the newest car could be. I wanted to make my children not be frightened of the world. And I think it worked in that they’re all incredibly creative people, my daughter is a brilliant, successful painter. That was the biggest thing I wanted to give them, not being frightened, as probably I had been.”

Vashti loves the young generation, their music, optimism and ideals, “they seem to be born with the instinct that war is not the way to go”, is besotted by the internet democracy, “where everyone has an equal chance”, perceiving the rise once more of the long-stifled voice of the maverick. Mention the old ‘indie’ ethos, “let a thousand flowers bloom” and she literally quivers in delight: “uuuuh!” This time around, she’s been sociable, met hundreds of musical like-minds, “and not a single person I haven’t got on with, I’m enjoying so much what they have to say”, seeing a tentative new belief in People Power, where “this young generation, probably more than the last couple, feel the power of collective consciousness”. This year, the sometime bush-dweller, vegetable apologist and singer too traumatised to sing has toured extensively, bolstered by Devendra’s sage advice; “he said, ‘you just have to do it until you don’t think about it anymore’. And that’s what I had to do. Where I’d said ‘no’ before I started to say ‘yes’. And it worked.” Next year, at the behest of another fan, David Byrne, ex-Talking Head, she’s playing a collective show (with Devendra) at New York’s Carnegie Hall, her response to which is a simple one: “aiieee!” She has one, lone regret.

“I never sang to my children,” she laments, “that really is my only regret. But now my grandchild is about to be born, maybe I’ll get another chance at that as well. They’ve even put a little CD player in his room. With my album on it. I’m not getting out of it this time!”

Here, dreamers of the world (and hopeless, ‘X Factor’ hopefuls) is a modern-day fable, a true-life, scenic-route testament to what “overnight success” can take.

“It’s never too late,” smiles Vashti, “you never know what’s round the corner.”

Yes, but don’t get too excited, ‘cos you never know what’s round the corner…

“Absolutely!” she guffaws. “While holding onto bits of wood, trying to save your life.”

Vashti Bunyan’s new album, Heartleap, is released on October 6.